Папера: этыка і эстэтыка

Гэты год я жыву ў аўстрыйскім Грацы. Аднойчы, блукаючы па ягоных вулках, я зайшла ў спецыялізаваную арт-краму, якіх тут шмат. У самым куце былі палічкі з белай паперай. Яна зачаравала мяне сваёй разнастайнасцю: фактура, адценне, таўшчыня. Я стаяла там і атрымлівала сваё эстэтычнае задавальненне, пакуль з сумам не ўзгадала пра радзіму.

Мой сум звязаны з рэчаіснасцю, у якой вымушаныя існаваць беларускія малыя, незалежныя выдавецтвы, а таксама, дзе вымушаная існаваць я, як аўтарка, для якой пытанне эстэтыкі – гэта і пытанне этыкі.

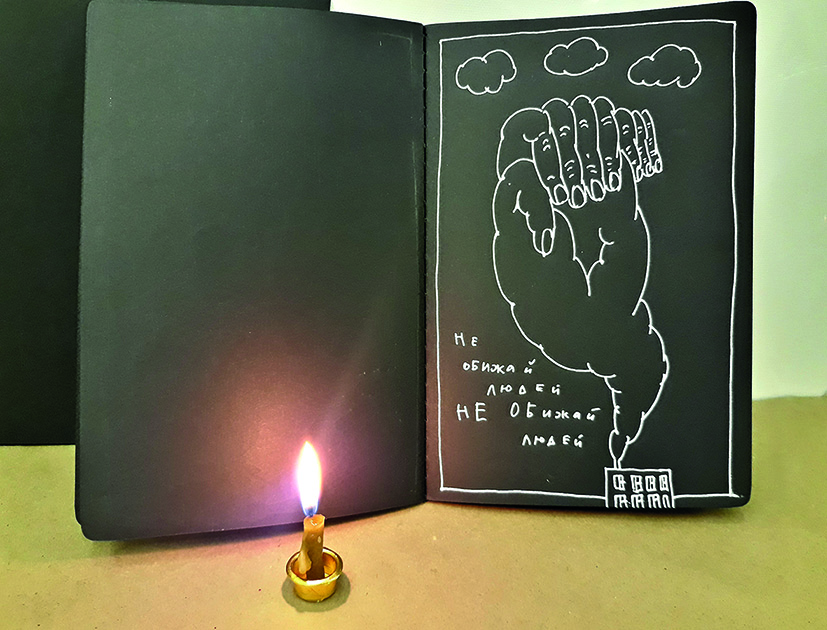

Для мяне кніжка ніколі не была толькі пра змест. Кніга – гэта яшчэ і “цела”, якое праз хаптыку і сэнсорыку выбудоўвае эмацыйную сувязь з чытачамі. Канешне, за савецкім часам, або ў часы перабудовы, калі шмат чаго было забаронена або дэфіцытна, мы заплюшчвалі вочы на тое, у якім выглядзе да нас прыходзілі веды. Аднак сёння ёсць мажлівасць чытаць і пры гэтым атрымліваць задавальненне не толькі ад зместу, але і ад формы.

Цяпер пра рэчаіснасць. У Беларусі знайсці добрую паперу для кніжкі – вялікая праблема. Беларуская папера лічыцца не вельмі якаснай, і большасць друкарняў закупляюць яе ў Расіі. На тое ёсць эканамічныя прычыны – мытны саюз, таму везці паперу адкуль танней і прасцей, чым з Літвы або Чэхіі. Малыя выдавецтвы (а менавіта яны друкуюць беларускамоўных сучасных аўтарак/аў) не могуць сабе дазволіць закупляць адмысловую паперу для сваіх кніжак, што і дорага і вымагае шмат сілаў для пераадолення бюракратычных перашкод, звязаных з перавозкай.

Да таго ж, падаткі на выдавецкую дзейнасць у Беларусі большыя за тыя ж у суседняй Расіі (20% і 13%, адпаведна). Тое ж тычыцца і коштаў на паліграфічныя паслугі: у Беларусі яны самыя вялікі ў параўнанні з усімі суседзямі. Калі я рыхтавала дзіцячую кніжку да друку, мая ілюстратарка прапанавала варыянт з інтэрактыўнымі элементамі, дзе можна нешта выцягнуць, або перасунуць на старонцы. Але ў выдавецтве адразу сказалі забудзьцеся. Нешта было зусім немагчыма для нашых друкарняў з тэхнічнага пункту гледжання, нешта – касмічна дорага.

Сітуацыю з паперай і паліграфіяй можна разглядаць як метафару беларускага кантэксту, дзе няма не толькі выбару паперы, але і ганарараў за выступы, падтрымкі перакладаў з беларускай мовы на замежныя, пісьменніцкіх рэзідэнцый, дзе нават за прыгажосць і эстэтыку ўсё яшчэ трэба змагацца.

Papier: Ethik und Ästhetik

Ich verbringe dieses Jahr in Graz. Auf einem meiner Spaziergänge bin ich einem Geschäft für Künstlerbedarf gelandet, wie es sie hier gleich mehrfach gibt. Ganz in der Ecke waren die Ständer mit dem weißem Papier. Ich war fasziniert von der Vielfalt an Texturen, Tönungen und Stärken. So stand ich dort und gab mich diesem ästhetischen Genuss hin, bis ich betrübt an Zuhause denken musste.

Meine Betrübnis hatte mit der Wirklichkeit zu tun, in der die kleinen, unabhängigen Verlage in Belarus überleben müssen und in der auch ich überleben muss als Autorin, für die ästhetische Fragen zugleich ethische Fragen sind.

Bücher waren für mich nie nur Inhalt. Bücher verfügen auch über einen „Leib“, der über Haptik und Sensorik eine emotionale Verbindung zu den LeserInnen herstellt. Freilich, zu Sowjetzeiten oder während der Perestroika, als Vieles verboten war oder Mangelware, konnten wir darüber hinwegsehen, in welcher Gestalt die Inhalte zu uns kamen. Heute ist es dagegen möglich, sich bei der Lektüre nicht allein am Inhalt zu erfreuen, sondern auch an der Form.

Nun zur Wirklichkeit: Gutes Papier für Bücher zu finden, ist in Belarus ein großes Problem. Belarussisches Papier gilt als nicht besonders hochwertig, die meisten Druckereien kaufen in Russland ein. Das hat auch ökonomische Gründe – wegen der Zollunion ist es günstiger und einfacher zu beziehen als Papier aus Litauen oder Tschechien. Kleinverlage (belarussischsprachige Gegenwartsliteratur wird vor allem in kleinen Verlage publiziert) können sich kein Spezialpapier für ihre Bücher leisten, da es zu teuer und die Überwindung der bürokratischen Hürden für die Einfuhr zu aufwendig ist.

Außerdem sind die Steuern für Verlagstätigkeit in Belarus höher als im benachbarten Russland (20% vs. 13%). Das gilt auch für die Druckkosten – sie liegen in Belarus über dem Niveau sämtlicher Nachbarländer. Als eines meiner Kinderbücher in Druck gehen sollte, schlug meine Illustratorin eine Ausgabe mit interaktiven Elementen vor, bei der man etwas herausziehen oder auf der Seite verschieben könnte. Aber im Verlag winkten sie gleich ab. Einige Lösungen waren für die hiesigen Druckereien technisch nicht umsetzbar, andere hätten horrende Kosten verursacht.

Die Papierproblematik und die Lage des Druckwesens können als Metapher für den belarussischen Kontext insgesamt gelesen werden, der nicht nur keine Papierauswahl bietet, sondern auch keine Auftrittshonorare, keine Übersetzungsförderung für belarussischsprachige Literatur, keine Aufenthaltsstipendien für SchriftstellerInnen und in dem selbst für Schönheit und Ästhetik immer noch gekämpft werden muss.

Übersetzung: Thomas Weiler

Paper: ethics and aesthetics

I am currently living in Austria’s Graz for a year. One day, walking through the streets of the town, I came to a specialised art shop, of which there are many. In the corner was a shelf with white paper. I was enchanted by the range: the textures, the shades, the thickness. I stood there, filled with the pleasure of it all, while sadly turning my thoughts to my homeland.

My sadness related to the fact that for small, independent Belarusian publishers, and for me, as an author, the question of aesthetics is necessarily also one of ethics.

For me, a book is never only about its contents. A book is also a ‘body’, which through the haptic and the sensory builds an emotional connection to its readers. Of course, in the Soviet period and during the time of perestroika, when many things were forbidden or scarce, we closed our eyes to the form in which knowledge came to us. Today, however, there is the possibility of reading and enjoying not only the content but also the form.

It’s only a possibility though. In reality, finding good paper for a book in Belarus is a big problem. Belarusian paper isn’t considered very high quality, and most printers buy instead from Russia. There are economic reasons for this – the customs union means that importing paper from Russia is cheaper and easier than from Lithuania or the Czech Republic. Small publishers (who are namely the ones publishing contemporary Belarusian authors) cannot afford to buy special paper for their books; it isn’t just expensive, it also requires a lot of effort to overcome bureaucratic obstacles relating to transportation.

In addition to this, publishing activities are taxed in Belarus far more than they are in neighbouring Russia (20% and 13%, respectively). Similarly, the price of printing services in Belarus are extortionate in comparison with those of all of its neighbours. When I was preparing to print a children’s book, my illustrator proposed interactive elements, flaps to pull or pieces to move around on the page. But our publisher immediately said, Forget it. It would have been quite impossible for us to print from a technical point of view, being astronomically expensive.

The situation with paper and the printing industry can be seen as a metaphor for the Belarusian context as a whole, where not only the choice of paper, but also performance fees, support for translations into foreign languages, writers’ residences, and even beauty and aesthetics still have to be fought for.

Translation: Annie Rutherford

Teilen

-

13 Samstag

17:04 Uhrweiter lesen | Volha Hapeyeva

PODCAST

Volha Hapeyeva: »Camel Travel« (Literaturverlag Droschl, 2021)

Moderation: Natascha Freundel

-

19 Dienstag

19:30 UhrPoint of No Return – Stimmen aus Belarus

Texte und Gespräche mit Iryna Herasimovich, Volha Hapeyeva, Artur Klinau, Zmicier Vishniou, Alhierd Bacharevič, Julia Cimafiejeva, Viktor Martinowitsch, Irina Bondas, Andreas Rostek, Thomas Weiler, Nina Weller und Tina Wünschmann

-

01 Mittwoch

Queer*East

Ein Festival mit Literatur, Musik Performance aus Mittel-, Ost- und Südosteuropa

-

08 Dienstag

Hausgäste

Alhierd Bacharevič, Volha Hapeyeva, Witalij Seroklinow und Julia Cimafiejeva in Lesung und Gespräch

Moderation: Thomas Weiler

Veranstaltungen mit Volha Hapeyeva

2021

März

Januar

2018

August

Mai