Rob Madole: »Pay the Piper«

Pay the Piper

Novel Excerpt

5.

From our seats near the front, I had to crane my neck to keep tabs on who was arriving with whom. The guest list was astonishing. We’d seen our fair share of star-studded concerts in New York and Paris, but nothing to rival this. Every direction you turned, your eyes landed on a musical titan. Directly behind us sat Pierre Boulez, chatting animatedly with Karlheinz Stockhausen. Next to them were the French composers Darius Milhaud and Gilbert Amy, looking tired and disinterested. Four rows back I noticed Igor Stravinsky; when his gaze intersected with mine, my consciousness momentarily blotted out. Had I really just locked eyes with the man who’d written The Firebird and The Rite of Spring? He was smaller than I’d ever imagined, peering around the hall with tiny birdlike movements, a blissfully unselfconscious expression on his face that could’ve only been forged from years of being the center of the world’s attention.

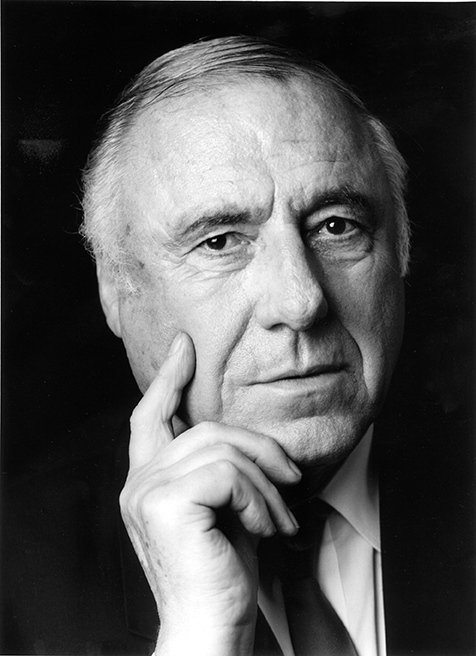

Engrossed in studying Stravinsky’s face, I almost failed to notice that sitting to his left was Elliott Carter, a composer whose work had made an enormous impression on me during my early Juilliard years—proving it wasn’t impossible for Americans to make music equaling the Continentals in ambition and intellectual rigor. He looked unremarkable in this grand setting, just another Yankee on holiday. Sitting to Stravinsky’s right was a man I didn’t recognize, although he projected an air of importance. He had brilliant white hair combed into a dramatic quiff above his head. Sitting straight in his seat, he towered over Stravinsky, and the two of them seemed to share an easy rapport, one of the man’s legs tapping playfully against Stravinsky’s chair. To my surprise, when the man caught me staring at him, he stared right back. A strange expression came over his face, almost as if he recognized me.

I turned quickly to the front. “Who is that?” I whispered to Lorrie.

“Who?” She turned around.

“Stop! Don’t be conspicuous.”

“How can I answer without looking?”

“Just be discreet.”

“I’m being discreet.” She pretended to smooth the back of her hair while examining from her peripheral vision. “Who am I looking for?”

“Next to Stravinsky,” I said. “The man with the white hair.”

“Oh, that’s Nabokov. Shin said he’s director of the festival.”

I knew the name. Nicolas Nabokov. My understanding was that he was a composer, but not a particularly successful one. He was better known as a festival organizer and professional gadabout, a fixture on the music scene in New York and Paris. We must’ve attended various concerts together, stood in the same reception halls, but that didn’t explain why he seemed to recognize me. My heart skipping, I glanced back furtively to see if he was still staring. He was. In fact, when we made eye contact, he smiled grandly, then leaned behind Stravinsky and whispered to Elliott Carter, who also gave me an appraising look.

Feeling a nudge in my ribcage, I turned back to the front. “Is that him?” Lorrie asked.

I followed her gaze. The evening’s headliners were entering the congress hall, banishing all thought of Nabokov. Four composers from around the world were debuting works that night. According to the program, the first three would be allotted fifteen minutes each. After that would come an intermission, then the hour-long performance of the work we’d all really come to see, the Stochastic Suite. A hush fell over the crowd as its composer took a seat a mere arm’s reach away from us: Iannis Xydakis.

“That’s him,” I said.

I stared. I couldn’t help it. My first glimpse of the maestro in the flesh. His face was enthralling, even more striking in person than in photographs. He had a bald, gleaming scalp, below which presided a craggy, protuberant forehead, bursting out at the temples like a misshapen potato. His nose was long and hawkish, flanked by stark cheekbones that loomed dramatically over his cheeks. Throwing everything into relief was the unforgettable scar, still a tumid pink in those days, slashing down the left side of his face like a jagged fork of lightning.

“He looks terrifying,” whispered Lorrie.

“He does,” I agreed.

“The scar is enormous.”

“It’s huge.”

“I don’t like him.”

“What?” I said, incredulous. “You haven’t even met him.”

She shook her head. “It’s the way you all worship him. He’s clearly a monster. I worry he’s mistreating Shin.”

“That’s ridiculous,” I whispered. “Maybe hear his music before you form an opinion.”

This was a habit of Lorrie’s, obsessing over an artist’s personality before engaging with his work. Scooting away, I leaned into the aisle, where I could get a better view of Xydakis.

As the concert began, I couldn’t tear my eyes off him. The first four works were short pieces for chamber groups that were serialist or total serialist in conception, clearly inspired by Messiaen and Boulez. While I listened, I tried to understand what had made these composers rise above the pack; what novelty or innovation in their compositions had recommended itself to the festival’s programmers. My initial reaction was to find the pieces interesting and well-performed. Watching Xydakis, however, made me question my judgement. Throughout the performances he grimaced and scowled, shaking his head in fits of pique. During the applause afterward, he’d join along listlessly, almost sarcastically, his claps out of sync with the crowd’s, his face twisted into a spiteful grin. I grew increasingly vexed by this. What did he hear that I didn’t? Did it make me a hopeless amateur if I failed to recognize what made these pieces so mediocre?

A brief intermission followed, during which Lorrie and I hardly spoke. She was too nervous about Takahashi, and I was too lost in thought. We couldn’t afford drinks from the concession stand, so we stood quietly in the foyer, staring impatiently at the clock.

When everyone was reseated in the concert hall, Takahashi took the stage. He entered in typically demure fashion, bowing hurriedly before cutting off the smatterings of applause by hastening to the piano. For a long while, he sat there silently, prepping himself for the performance. My eyes were locked on Xydakis during this quiet interval. He was hunched in his seat, elbows resting on his knees so he could cradle his forehead in his hands. His fingers massaged his scalp tensely as he fixed an unblinking stare at the stage. It seemed like he was mouthing something to Takahashi, but Takahashi didn’t look over at him. Gazing rigidly at his hands, Takahashi took one final, deep breath. Then he began to play.

How can I convey the experience of witnessing Takahashi’s performance? It was unlike anything I’d seen before. According to the program notes, Xydakis had composed the Stochastic Suite “stochastically,” that is to say at random, by inputting certain probability fields into a punch-card computer housed at the Technical University in Berlin. The computer then generated the score on the basis of the chosen probability fields, meaning that any note within a given field could be located at any point of the piece at any time. The composition’s only overarching “axiom” was that every tone had to be held for one half-second—a nod to the “inexorability of time’s passing,” in the words of the program.

What this meant in practice was that Takahashi’s job was to advance forward at an unrelenting tempo while playing notes and chords essentially at random, generating an onslaught of sound. To the audience, he looked like a man yoked to a chain that was being jerked, thrashed, whipped about by an unseen tormentor. Meanwhile Xydakis sat only a few feet away from him, glaring fiendishly at the piano. It was a mesmerizing sight. The impression was that of a storm of brain matter emanating from Xydakis and being beamed up to Takahashi onstage, where it made him convulse about the piano as if by telepathic relay. In its most clear distillation, I realized, this was a metaphor for Xydakis’s genius – for the force of personality it required to manipulate sounds and bodies in space, to compose music. It was a force that I, for whatever reason, had yet to discover within myself.

Takahashi’s commitment to the performance was astonishing. Now I understood why Xydakis had been so excited when he came across Takahashi in the Conservatoire’s practice room—the performance was only made possible through Takahashi’s sheer force of will, his determination to fulfill the tyrannical demands of the inhuman machine that had composed the score. By the twentieth minute, his knuckles had begun to bleed from striking the keys’ edge too many times. His hair was clinging to his forehead, soaked with a feverish sweat. By the fortieth minute, foam had begun accumulating at the edges of his lips. His eyes had gone vacant, rolled up in their sockets like a man in a trance. When precisely sixty minutes had elapsed, Takahashi struck one final chord, held it for nearly five seconds, then collapsed in his seat, extinguished.

The crowd was stunned. Some in the audience, I can only imagine, were uncertain whether the concert was finished or whether Takahashi had just expired in front of their eyes. It took a moment before anyone dared to clap. Soon this brave soul was joined by another, and another, and eventually the whole crowd erupted into a dazzling ovation. Only as the audience stood in rapture did Takahashi suddenly rise from the piano, a man awakened from the dead. Sheepishly, he gave a small wave. Then he walked offstage. The applause continued for another five minutes, dragging him out for two more bows.

To get a glimpse of Xydakis around the throng of bodies, I had to stand on my tip-toes. I was surprised to find that he was still seated, as if refusing to acknowledge the crowd’s approval. As if he were almost offended by it. He stared ahead fixedly, an indignant look in his eyes, muttering to himself.

“Unbelievable,” I said, turning to Lorrie.

To my surprise, she was nowhere to be found.

Rob Madole is a writer and translator. Born in 1987 in Dallas, Texas, he has lived in Berlin since 2010. His essays and reviews have appeared in publications such as the New York Times Magazine, The Baffler, Texas Monthly, The Point Magazine, Ploughshares, Spike Art Magazine, The Los Angeles Review of Books, and elsewhere. He was formerly an editor at the architecture magazine ARCH+. Currently, he is working on a novel about the midcentury avant-garde and its entanglements with the so-called ›cultural Cold War‹.