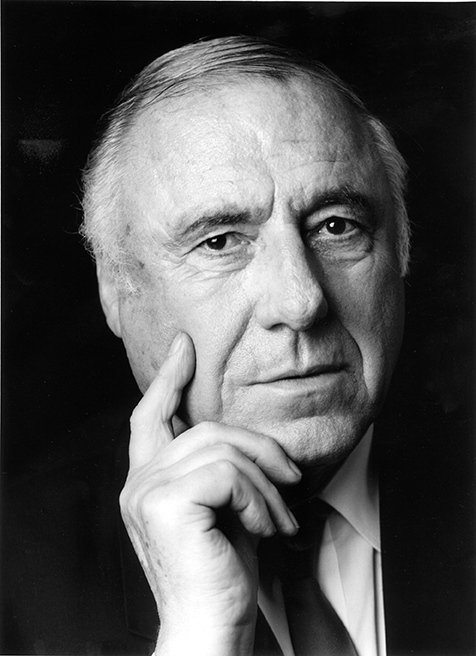

Kenny Fries: »The Behavior of the Delinquents«

The Behavior of the Delinquents

My first visit to the Aktion T4 killing site at Brandenburg an der Havel was in autumn. My destination, where 9,000 disabled people were murdered as part of the Nazi “euthanasia” program, is embedded in the activities of the town—trams and buses, stores, a bank, a cafe.

The buildings that were once the old prison were mostly destroyed during the war. If not for dark gray letters painted on one side of the light gray building – GEDENKSTÄTTE, on one side, and its English translation, MEMORIAL, on another—the site could easily be passed unnoticed. From a distance, it looks prefab, temporary, perhaps an ad hoc extension to an overcrowded school or municipal department.

Though it was October, I was thinking of winter. At the Nuremberg “Doctors’ Trial” in 1947, Viktor Brack—the economist, SS officer and head of the office of the Chancellery of the Führer who was in charge of Aktion T4—testified that the first of the mass murders of disabled people happened “in snow-covered Brandenburg on a winter’s day in December 1939 or January 1940.” The exact date of this “test killing” has not yet been determined.

No documents from the “test killing” have been preserved. According to information at the memorial, “Who the murdered patients were and where they came from is unknown.” What is known comes primarily from postwar testimony of those involved, or thought to be involved, in what took place that day.

Unlike the Holocaust, there are no T4 survivors. We know about T4 and its aftermath mainly through medical records and from the perpetrators. Aktion T4 does not have its Elie Wiesel or Primo Levi.

That is the main reason I write about what happened to disabled people during the Third Reich. I want to be what Susanne C. Knittel and other scholars call a “vicarious witness.” Ms. Knittel describes this not as “an act of speaking for and thus appropriating the memory and story of someone else but rather an attempt to bridge the silence through narrative means.” This is my way of bridging the silence, of keeping alive something that is too often forgotten.

I’m not surprised that some of the perpetrators’ testimony is contradictory. In his diary, Dr. Irmfried Eberl, the medical director at Brandenburg, mentions Jan. 18, 1940, as the date of the “test killing.” However, Dr. Horst Schumann, whom we know to have been present at the event, was on that day at Grafeneck, where he would oversee mass killings, the first of which occurred on Jan. 18. Another T4 employee said the murder of patients in Grafeneck started “about 14 days” after the “test killing” in Brandenburg. It seems Eberl mixed up the dates of the two killings.

After he was arrested in 1959, Werner Heyde, a psychiatrist and the medical director of the T4 program, placed the “test killing” at the “beginning of January 1940.” Heyde confessed to being only an observer.

The German Meteorological Office records the first major snowfall of the 1939-40 winter in Brandenburg on New Year’s Eve, 1939; December had been relatively dry. Brack, in his testimony, was very clear about the snow on the ground at Brandenburg for the “test killing.” By deduction, it seems that the first Brandenburg mass murder took place during the first days of January 1940.

Though the exact date is somewhat speculative, the words of those responsible for the murder of 70,000 disabled people in Aktion T4, and the 230,000 killed after the program’s official end, clearly speak to the main cause for what happened: the disvaluing of disabled lives. Eugenics, which was rampant before and during the Reich, provided the rationale for the killings, stigmatizing those with disabilities as not human.

Dr. Albert Widmann, a chemist, forensic scientist and head of the chemical department of the central offices of the Reich Detective Forces, testified that he was asked to procure poison in large quantities. At a meeting with an unidentified representative of the Chancellery of the Führer, Widmann asked, “What for? To kill people?”

“No,” was the reply. “Animals in the form of humans.”

It was the police chemist Dr. August Becker who prepared the carbon monoxide gas for what he called the “euthanasia experiment.” Testifying in the 1960s, Becker also echoed eugenic depictions of the disabled. He recalled looking through the gas chamber peephole and observing “the behavior of the delinquents,” as the gas filled up the chamber and the victims’ lungs. Becker’s depiction likens disabled people to the immoral and illegal.

Becker described, in detail, the gas chamber as “a room similar to a shower room, lined with tiles about three by five meter[s], and three meters high in size.” According to Becker, between 18 and 20 patients were led by nurses into this “shower room.” These men had to “undress in an anteroom, so they were totally naked.” Becker pointed to Widmann as the one who “operated the gas installation.” But Widmann always denied taking part.

When interrogated in 1947, Richard von Hegener, deputy head of the killing of disabled children, named “the chemist in charge, Dr. Becker” as the one “who let the CO gas into the room.” Von Hegener said there were 30 patients “dressed only in institutional clothing,” who “were led in and they calmly took a seat on the benches in the room without any resistance.” Heyde stated there were “10, at most 15—the figure was more than 10—mentally ill patients.” He said, “I don’t really know who let the gas in.”

According to Brack, there were “four such patients,” all men, whom he described, in another eugenic nod, as “incurable.” When asked about their ages or from which institutions they came he replied, “I really don’t have any memory of that any more.”

The more I learn, the more I understand the connection between Aktion T4 and what happened later to Jews and others deemed “undesirable.” The Brandenburg “test killing” demonstrated that gassing was a “suitable” means for mass murder.

And as the text at the memorial emphasizes, “it also gave the future ‘killing doctors’ the chance to familiarize with the method.” After recommending carbon monoxide for the mass murder of the disabled, Widmann developed the gas wagons that were used for the subsequent mass murder of Jews on the war’s eastern front. Becker helped design these mobile killing units, including those used by the notorious Einsatzgruppen in the Nazi-occupied areas of the Soviet Union. Eberl later worked at the Chelmno and Treblinka extermination camps during Operation Reinhard, the “Final Solution.”

Of those whose testimonies are highlighted at the Brandenburg memorial, Brack, in 1948, was the only one executed. Von Hegener was arrested in 1949 and sentenced to life imprisonment but was released early. Becker had a stroke in 1959 and was deemed unfit to stand trial. Heyde was arrested in 1959 and committed suicide before his trial. In both 1962 and 1967 Widmann was convicted to serve several years in prison but was released upon payment of a fine.

Outside the memorial building, there is no cemetery. Across a parking lot lies a large plot of gray gravel, interrupted only by the reddish-brown brick foundations of what was the prison barn, which housed the gas chamber. There are circles of piled leaves among the gravel—as if these random forms were gathered in a subliminal ritual of mourning.

Kenny Fries is the author of »In the Province of the Gods« (Creative Capital Literature Award); »The History of My Shoes and the Evolution of Darwin’s Theory« (Outstanding Book Award, Gustavus Meyers Center for the Study of Bigotry and Human Rights); and »Body, Remember: A Memoir«. He edited »Staring Back: The Disability Experience from the Inside Out« and his books of poems include »In the Gardens of Japan, Desert Walking, and Anesthesia«. He was commissioned by Houston Grand Opera to write the libretto for »The Memory Stone«. Twice a Fulbright Scholar (Japan and Germany), he was a Rockefeller Foundation Bellagio Center Arts and Literary Arts Fellow; a Creative Arts Fellow of the Japan/US Friendship Commission and the National Endowment for the Arts; a Cultural Vistas/Heinrich Böll Foundation DAICOR Fellow in transatlantic diverse and inclusive public remembrance; and is a Ford Foundation/Mellon Foundation/USA Artists Disability Futures Fellow. He has received grants from the DAAD, Canada Council for the Arts, Ontario Arts Council, and Toronto Arts Council. He curated ›Queering the Crip, Cripping the Queer‹ the first international exhibit on queer/disability history, activism, and culture at the Schwules Museum Berlin. His work-in-progress is »Stumbling over History: Disability and the Holocaust«, excerpts of which have been published in The New York Times, The Believer, and Craft, and are the basis of his video series »What Happened Here in the Summer of 1940?«.