Siamo Soli Noi*

Aujourd’hui c’est le 14 janvier 2021 et dix ans se sont écoulés depuis la révolution des tunisiens.

Depuis, je n’ai plus trente ans mais 40 ans !

40 ans c’est l’âge de la retraite pour les footballers. C’est là qu’ils se retrouvent sur la touche. Que s’est-il passé en 10 ans en Tunisie ?

Presque pas grand-chose : des manifestations et des grèves au quotidien et le football qui est omniprésent dans ce pays.

Le seul défouloir des jeunes des cités est le foot, aller au stade, chanter la gloire de leurs équipes, ou dessiner des fresques monumentales près des terrains vagues à l’effigie de leurs équipes comme on le fait à Belfast ou à Gaza pour célébrer les sections militaires ou pour rendre hommage aux martyrs.

Même pour se balader en ville, les jeunes tunisiens mettent les maillots de leur équipe favorite, ceux qui rêvent de quitter le pays par n’importe quel moyen, mettent le maillot d’une équipe européenne afin de rêver d’un ailleurs.

Les confrontations qui ont eu lieu la nuit du 15 janvier de 2021, malgré le confinement et un couvre-feu qui commence à 16h, n’est qu’une guerre sociale qui ne dit pas son nom. C’est l’expression de la colère longtemps réprimée face à une classe politique corrompue qui ne pense aux jeunes qu’en temps d’échéances électorales.

L’année dernière, un jeune de 17ans voulant échapper aux matraques des policiers, se noie dans le canal sous les yeux de policiers qui ont refusé de lui venir en aide malgré ses cris : « je ne sais pas nager ! je ne sais pas nager ! »… Il est mort noyé.

Comme dans chaque match de foot qui se respecte, il y un aller et un retour ! Le début de cette année sonne comme le match de la revanche. Et aujourd’hui, c’est l’appareil sécuritaire qui s’invite dans le terrain de ces jeunes, chez eux dans leurs quartiers dont ils connaissent la moindre ruelle. Ils peuvent donc facilement deviner quand il faut passer en attaque et le moment où il faut être en défense.

Les bombes lacrymogènes ont remplacé le ballon que les jeunes cagoulés n’hésitent pas à remettre au camp de l’adversaire, laissant pour la plupart du temps les forces de l’ordre en hors-jeu.

L’aube commence à pointer, les deux camps commencent à se retirer. Les premiers travailleurs qui bravent le froid de cet hiver auront un peu de mal à décerner le brouillard matinal des fumées des bombes. Le match reprend le soir juste après le journal télé de 20 heures et le bal des déclarations des politiciens. Les jeunes des banlieues ne connaissent pas le découragement malgré les centaines d’arrestations, l’humiliations, les mutilations, l’injustice, la prison… et un avenir déjà incertain qui va cesser d’exister…

* Nous sommes seuls. Un jeu de mots d’un slogan du football italien “Siamo solo noi” (Il existe que nous).

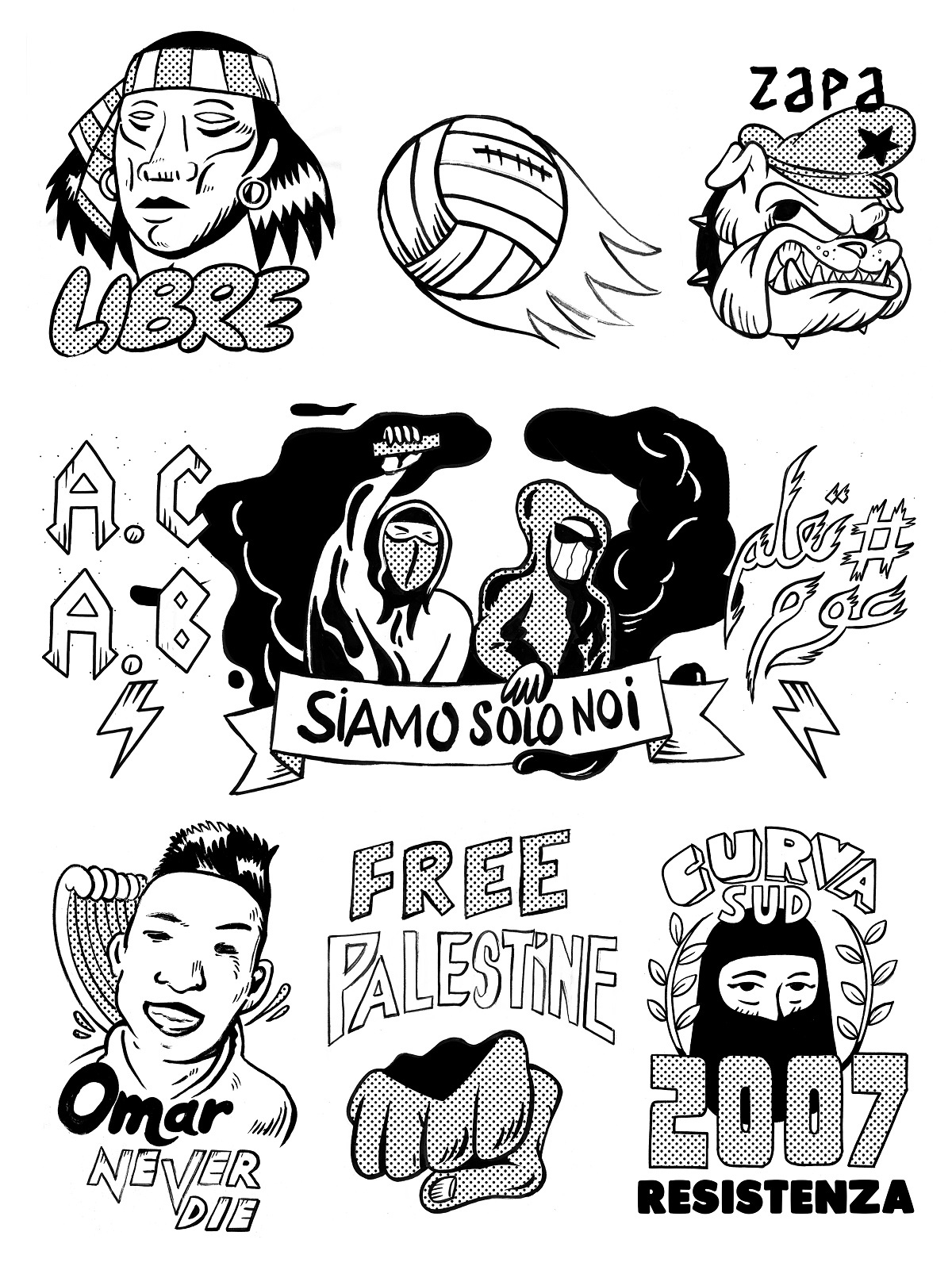

** L’hashtag en arabe dans l’illustration : #Apprends à nager . Mes illustrations sont une sorte de tableau qui compile des dessins, des tags et des slogans que les jeunes des cités, supporters des grandes équipes nationales de foot apposent sur les murs de leurs quartiers.

Siamo Soli Noi*

Heute ist der 14. Januar 2021 und seit der Revolution der Tunesier sind zehn Jahre vergangen.

Jetzt bin ich nicht mehr 30, sondern 40 Jahre alt!

Für Fußballer ist 40 das Renteneintrittsalter. Dann finden sie sich auf der Ersatzbank wieder.

Was ist in diesen zehn Jahren in Tunesien passiert?

Fast nichts: tagtäglich Demos, Streiks und Fußball, der in diesem Land allgegenwärtig ist.

Abreagieren können sich die Jugendlichen aus den armen Vorstädten nur beim Fußball, wenn sie ins Stadion gehen, ihre Mannschaften besingen oder in der Nähe von Baulücken monumentale Fresken ihrer Mannschaften malen, wie man es in Belfast oder Gaza tut, um Militäreinheiten zu feiern oder Märtyrern zu huldigen.

Selbst wenn sie einfach nur durch die Stadt bummeln, ziehen tunesische Jugendliche die Trikots ihrer Lieblingsmannschaft an. Wer davon träumt, das Land auf welche Art auch immer zu verlassen, zieht das Trikot einer europäischen Mannschaft an, um sich an einen anderen Ort zu träumen.

Die Zusammenstöße, zu denen es in der Nacht vom 15. Januar 2021 trotz Lockdown und Ausgangsperre ab 16h gekommen ist, sind ein sozialer Krieg, den man nicht beim Namen nennt. Er ist Ausdruck einer lange unterdrückten Wut auf eine korrupte politische Klasse, die immer erst kurz vor dem Wahltag an die jungen Menschen denkt.

Letztes Jahr ist ein 17jähriger Jugendlicher beim Versuch, den Schlagstöcken der Polizisten zu entkommen, unter den Augen eben jener Polizisten im Kanal ertrunken. Sie hatten sich geweigert, ihm zur Hilfe zu kommen, obwohl er „Ich kann nicht schwimmen! Ich kann nicht schwimmen!“ geschrien hatte… Also ist er ertrunken.

Wie bei jedem anständigen Fußballspiel gibt es ein Hin- und ein Rückspiel. Dieser Jahresanfang klingt wie das Revanchespiel. Jetzt ist es der Sicherheitsapparat, der ungebeten auf dem Spielfeld der Jugendlichen erscheint, in ihren Vierteln, in denen sie jede noch so enge Gasse kennen. Daher fällt es ihnen leicht zu erraten, wann sie zum Angriff übergehen und wann in die Defensive gehen müssen.

Das Tränengas hat den Fußball ersetzt, den die vermummten Jugendlichen ohne Zögern ins gegnerische Feld schießen, wobei sie die Ordnungskräfte die meiste Zeit über ins Abseits manövrieren.

Die Morgendämmerung bricht an und beide Lager beginnen, sich zurückzuziehen. Den ersten Berufstätigen, die der Kälte dieses Winters trotzen, wird es ein bisschen schwerfallen, den morgendlichen Nebel von den Tränengasschwaden zu unterscheiden. Abends, direkt nach den 20-Uhr-Nachrichten im Fernsehen und den Erklärungskonzerten der Politiker, wird die Partie wiederaufgenommen. Die jungen Menschen aus den Vorstädten sind nicht zu entmutigen, trotz hunderter Festnahmen, Erniedrigungen, Verstümmelungen, trotz Ungerechtigkeit und Gefängnis… und einer ohnehin schon unsicheren Zukunft, die es bald nicht mehr geben wird…

*Wir sind allein. Wortspiel mit dem italienischen Fußballslogan „Siamo solo noi“ (wir sind’s nur).

**Arabischer Hashtag in der Illustration: #LernSchwimmen. Meine Illustrationen sind eine Art Tableau, das Zeichnungen, Tags und Slogans vereint, mit denen jugendliche Fußballfans aus den Vorstädten die Mauern ihrer Viertel verzieren.

Übersetzung: Lilian Pithan

Siamo Soli Noi*

It is 14 January 2021 and ten years have passed since the Tunisian Revolution.

I’m not thirty any more; I’m forty!

Forty is the age of retirement for footballers. The age when they’re sidelined. What has happened in Tunisia in those ten years?

Not a lot: everyday protests and strikes—and the inevitable football, ubiquitous in this country.

Football is the only outlet for young people on estates: going to the stadium, chanting to the glory of their teams and spraying huge frescos of them on the edge of wasteland, like the pictures sprayed in Belfast or Gaza to celebrate military squads or pay homage to martyrs.

Young Tunisians don the shirt of their favourite team even for a walk around town—and those desperate to get out of the country wear the shirt of some European team and dream of a life elsewhere.

The confrontations that took place on the night of 15 January 2021, despite the 4 p.m. curfew, were a social war in all but name—the expression of a long-repressed anger at a corrupt political class that has no thought for young people unless elections are imminent.

Last year, a young man of seventeen who was trying to escape police truncheons drowned in the canal in full view of the police who refused to go to his help despite his cries of ‘I can’t swim! I can’t swim!’ He died in the water.

As with every self-respecting football match there is a home and away game. The start of this year looks like a revenge match. This time, the security apparatus has invited itself to the home ground of Tunisia’s young people—into the neighbourhoods where they are familiar with every alleyway and will have no trouble knowing when to attack and when to defend.

Tear bombs have taken the place of the ball, and the young people in balaclavas have no qualms about putting them back on the opponent’s side of the field, leaving the forces of law and order largely offside.

Day dawns; both sides begin to retreat. The first workers to brave the winter’s cold will have trouble distinguishing the early-morning mist from the tear gas. The match is resumed in the evening just after the eight-o’clock news and the politicians’ dance of statements. The young people of the estates are undeterred, despite the hundreds of arrests, the humiliations and mutilations, injustice, imprisonment—and an already uncertain future that is on the verge of disappearing.

* We are alone. A pun on the Italian football slogan “Siamo solo noi” (It’s just us).

** The Arabic hashtag in the illustration reads: #LearnToSwim. My illustrations are a kind of montage of some of the drawings, tags and slogans sprayed on neighbourhood walls by estate kids who support the big national football teams.

Translation: Imogen Taylor

وحيدون هم نحن*

اليوم هو الرابع عشر من يناير وها قد مضى عشر سنوات من اندلاع ثورة التونسيين.

ومنذ ذلك الحين، لم أعد في الثلاثين من عمري بل 40 عامًا.

في سن الأربعين يحال لاعبو كرة القدم على المعاش حيث يجدون أنفسهم على حافة خط التماس.

ولكن ما الذي حصل في تونس خلال السنوات العشر المنصرمة؟

لا شيء يذكر تقريبا سوى احتجاجاتٍ وإضراباتٍ يومية ومباريات كرة قدمٍ تجرى ولا تكاد تنقطع في مختلف ارجاء هذا البلد.

منفذ شباب المدن الوحيد هو كرة القدم، أو بالأحرى الذهاب إلى الملعب لمتابعة المباريات وترديد أناشيدٍ تمجد فرقهم،

أو رسم اللوحات الجدارية الضخمة المحاذية للأماكن المقفرة ومداخل الاحياء الفقيرة للاحتفاء بفرقهم كما هو الحال في بلفاست أو غزة تخليدًا لذكرى الكتائب المقاتلة أو تكريمًا للشهداء.

حتى عندما يجوبون شوارع المدينة، يرتدي جلّ شباب تونس قمصان فرقهم المفضلة أما أولئك الذين يحلمون بمغادرة البلاد بأي وسيلة ما فهم يرتدون أقمصة فرق أوروبية من أجل مواصلة حلمهم للعيش في مكان اخر حيث يظل الحلم ممكنا.

المواجهات التي اندلعت ليلة الخامس عشر من يناير 2021 بالرغم من فرص حجر صحي مفاجئ وحظر جولان ينطلق عند الرابعة بعد الظهر هو في حقيقة الأمر حرب لا تعلن اسمها خلفياتها اجتماعية بالأساس. هي تعبير غاضب لطالما وقع كتمه ضد طبقة سياسية مرتشية لا تتذكر هؤلاء الشبان سوى زمن الاحتياجات الانتخابية.

في العام الفارط قضى شاب يبلغ من العمر 17 سنة نحبه غرقًا في نهر محاذي لأكبر ملاعب العاصمة عندما حاول الهرب من هراوات الشرطة الغليظة. مات عمر غرقا وهو يصرخ „لا اعرف السباحة، لا اعرف السباحة “ تحت على مسامع وانظار اعوان الشرطة الذين رفضوا مساعدته… بل وكان ردهم „تعلم العوم“

من المتعارف عليه في مباريات كرة القدم أن يكون هناك لقاء ذهابٍ واخر إياب!

بداية هذه السنة ينذر بمقابلة الثأر. واليوم يستضيف هؤلاء الشبان القوى الأمنية في ملعبهم الخاص، انهم يعرفون جيدا

شوارعهم وعموم تفاصيله. يعلمون جيدا متى وجب عليهم الهجوم ومتى يتحتم عليهم الرجوع الى خطوط الدفاع.

قنابل الغاز المسيلة للدموع عوضت كرة اللعب حيث يعيد الشباب المقنعون إعادة قذفها في ملعب الخصم تاركين قوات حفظ الامن تتخبط في التسلل.

تتسلل خيوط الفجر الاولى معلنة نهاية الليل. العمال الذين تحدوا برد الشتاء للخروج لمصانعهم لا يكادون ان يميزوا بين ضباب الصباح الكثيف ودخان قنابل الغاز الثقيل. ستتجدد المقابلة مساءًا بعد نشرة أخبار الثامنة ليلاً وكورال تدخلات السياسيين. شباب الاحياء لا تعرف الهزيمة ولا الاحباط بالرغم من سلسلة الاعتقالات والإذلال المهين وإنزال الألم بهم أو عمليات الظلم المنهج والسجن … ومستقبل غير معلوم بات منعدما…

*جملة في أصلها إيطالية يشعلها البعض شعار حياة تصاحب رسوم شبانًا مقنعين تختزل وحدتهم كشباب مهمش يتعرض لعنف الشرطة دون ان يكترث باقي المجتمع لما يلاقونه من ظلم ممنهج.

** الهاشتاغ #تعلم عوم تجاوز حلقات مشجعي كرة القدم ليصبح صرخة احتجاج يفضح عنف الشرطة في تونس.

الرسوم المصاحبة مستوحاة من التعابير الفنية وشعارات أنصار فرق كرة القدم التونسية الكبرى.

ترجم النص من الفرنسية إلى العربية قبل المؤلف

Teilen