Meeting Death

My coming to this world was connected with the difficulties of my mother giving birth – soon after delivering me, she had a near-death experience. She claimed that, while hovering in her eternal body at a point just below the ceiling, she was able to see her doctors trying to revive her. A few moments later she returned to her body. Funny, she only told me about it when I was a teenager. Still, I was wondering if something inside me was aware of what was happening.

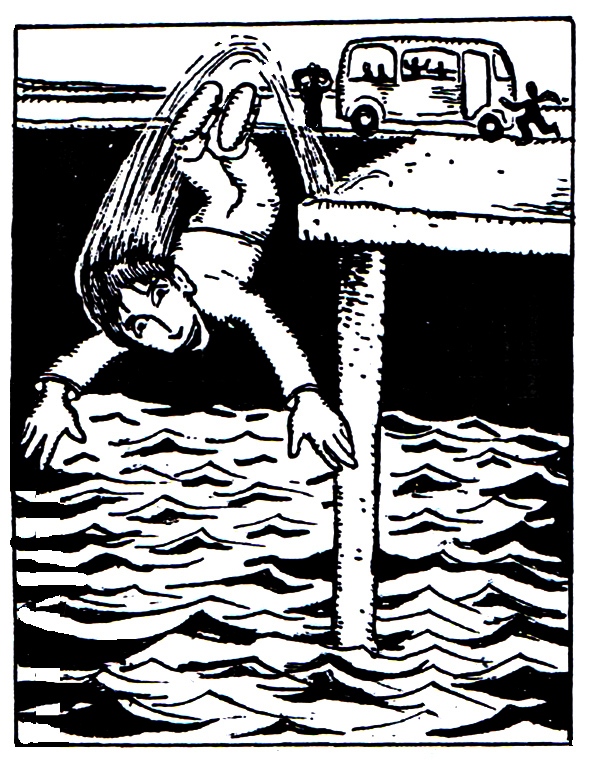

An even more strange memory came back a few years ago, while my parents were still alive, and I was telling them how I enjoyed our trip to the Adriatic seaside, and the island of Korčula, when I was five years old. Everything was so bright in my memory; I still remember all the joys of the beach and the sun. Their reaction was surprising – they told me that it was their worst nightmare. How come? Because, when the bus reached the seaside, I immediately ran to a platform and jumped into the deep sea. The whole bus was screaming in horror, and my father jumped after me in his clothes; they didn’t know if I would survive this. I was appalled. My brain obviously erased this incident from my memory. How I decided to jump into possible death, at that age, is beyond comprehension.

Another encounter with death happened when I was about 20 years old and had to serve for a year and a half in the Yugoslav People’s Army, like every young male at that time. It was such a pain in the ass, since a lot of the exercises were accurate re-creations of the heavy military operations during the struggle of WW2 (even then in the 1980s, it was way too anachronistic). In the cold of December, we were sent on a 70 km march into the Bosnian mountains, and we had to hoist a tent over a one meter deep hole that we dug in the ground. That hole was where we had to sleep during the night… I remember, for two nights, trembling with cold, before a moment when I entered a strange kind of bliss, a Nirvana-like state where I didn’t feel cold any more… It was rudely interrupted by the soldiers who were coming to wake us up. When, years later, I told this to a friend who works as a medical technician, he pointed out that I was actually experiencing moments before dying – in the final phase before freezing to death, the body uses all its reserves of energy.

So, these were my modest encounters with Death… And I was thinking recently about how personal experiences are connected to concepts conceived by the collective. For example, by living in Serbia, I’m able to understand that technology, fashion, cultural trends, and many other things, are modelled in developed countries, and then imitated in the peripheral parts of the world such as the Balkans. This places the collective minds of small countries into an inferior position: some of them believe that they are bound to stay epigones forever, and – rather than searching for their own way of solving problems – they wait passively for solutions to come from somewhere else. It was clearly visible during the global panic caused by Covid-19 – although it started in China, the response to pandemics were obviously projected in the West. In countries such as Serbia, they would wait, and then just do what the others were doing. That’s what makes this pandemic a global phenomenon, jumping borders and crossing cultures.

And even if it was to be expected, to me it was interesting to observe how this situation raised the fear of dying. Because – let’s be honest – death is not often discussed in the Western world. The possibility of dying of some mysterious pestilence, alone and isolated, far from your comfortable home and surrounded by people in ‘space suits’ (who treat you like a pest!), seems to be raising peoples’ worst fears…

Begegnungen mit dem Tod

Ich kam nicht leicht auf diese Welt. Kurz nach meiner Geburt gab es Komplikationen. Meine Mutter hatte eine Nahtoderfahrung. Sie behauptete, dass sie, während sie in ihrem unsterblichen Körper an einem Punkt knapp unter der Decke schwebte, ihre Ärzte sehen konnte, die versuchten, sie wiederzubeleben. Ein paar Augenblicke später kehrte sie in ihren Körper zurück. Komisch, sie erzählte mir erst davon, als ich ein Teenager war. Trotzdem fragte ich mich, ob etwas in mir das schon wusste.

Eine noch seltsamere Erinnerung kam vor ein paar Jahren zurück. Meine Eltern lebten damals noch und ich erzählte ihnen, wie ich unsere Reise an die Adria und auf die Insel Korčula genoss, als ich fünf Jahre alt war. Alles war so hell in meiner Erinnerung. Ich erinnere mich noch, wie viel Freude mir Strand und Sonne machten. Ihre Reaktion war überraschend: Sie sagten, dass es ihr schlimmster Albtraum war. Warum? Weil ich sofort, als der Bus an der Küste ankam, zu einer Plattform rannte und ins tiefe Meer sprang. Der ganze Bus schrie vor Entsetzen, und mein Vater sprang mir in seiner Kleidung hinterher. Sie wussten nicht, ob ich das überleben würde. Ich war entsetzt. Mein Gehirn hatte diesen Vorfall offensichtlich aus meinem Gedächtnis gelöscht. Wie ich mich in diesem Alter dazu entschlossen hatte, in den möglichen Tod zu springen, ist unbegreiflich.

Mit etwa 20 hatte ich eine weitere Begegnung mit dem Tod. Ich musste damals eineinhalb Jahre zur Jugoslawische Volksarmee – wie jeder junge Mann. Es war eine Qual, weil viele der Übungen exakt den schweren Militäreinsätzen im Zweiten Weltkrieg nachempfunden waren (das passte schon in den 1980ern nicht in die Zeit). In der Dezemberkälte wurden wir auf einen 70 km langen Marsch in die bosnischen Berge geschickt, und wir mussten ein Zelt über einem ein Meter tiefen Loch aufstellen, das wir selbst gruben. In diesem Loch mussten wir nachts schlafen … Ich erinnere mich, dass ich zwei Nächte lang vor Kälte zitterte, bevor ich eine seltsame Art von Glückseligkeit erreichte, einen dem Nirvana ähnlichen Zustand, in dem mir nicht mehr kalt war … Er wurde unsanft von den Soldaten unterbrochen, die kamen, um uns zu wecken. Jahre später erzählte ich einem Freund davon, der Medizintechniker war. Er meinte, dass ich tatsächlich Momente vor dem Sterben erlebt hatte – in der Endphase vor dem Erfrieren verbraucht der Körper all seine Energiereserven.

Das waren also meine bescheidenen Begegnungen mit dem Tod … Und ich habe letztens darüber nachgedacht, wie persönliche Erfahrungen mit kollektiven Konzepten verbunden sind. Ein Beispiel: Wenn ich in Serbien lebe, kann ich verstehen, dass Technologie, Mode, kulturelle Trends und viele andere Dinge aus Industrieländern kommen und dann in den peripheren Teilen der Welt, wie dem Balkan, nachgeahmt werden. Das bringt das Kollektivbewusstsein in kleinen Ländern in eine untergeordnete Position: Einige glauben, dass sie für immer Epigonen bleiben müssen. Anstatt Probleme auf ihre eigene Art zu lösen, warten sie passiv darauf, dass Lösungen von woanders kommen. Das sah man deutlich während der globalen Panik, die Covid-19 auslöste. Auch wenn es in China losging, wurde die Reaktion auf Pandemien offensichtlich in den Westen projiziert. In Ländern wie Serbien wartete man ab und tat dann einfach, was die anderen taten. Das macht diese Pandemie zu einem globalen Phänomen, über Grenzen und Kulturen hinweg.

Und auch wenn es zu erwarten war, war es für mich interessant zu beobachten, wie die Angst vor dem Sterben in dieser Situation größer wurde. Denn – seien wir mal ehrlich – über den Tod wird in der westlichen Welt nicht oft gesprochen. Die Möglichkeit, an einer mysteriösen Seuche zu sterben, allein und isoliert, weit weg von deinem gemütlichen Zuhause und umgeben von Menschen in „Raumanzügen“ (die dich wie eine Plage behandeln!), scheint die schlimmsten Ängste der Menschen zu wecken …

Übersetzung: Iris Thalhammer

Susreti sa smrću

Moj dolazak na svet bio je povezan sa teškim porođajem, tako da je moja mama doživela kliničku smrt odmah nakon što sam se rodio. Tvrdila je da je njen duh odlebdeo negde ispod plafona bolničke prostorije, odakle je mogla da posmatra doktore dok su pokušavali da je ožive. Nakon nekog vremena, vratila se u svoje telo. O tome mi je pričala tek kad sam bio u tinejdžerskom dobu. Ipak, pitao sam se da li je nešto u meni ipak bilo svesno toga što se dešavalo.

Još neobičniji uvid desio se pre nekoliko godina, dok su moji roditelji još bili živi, a ja sam im pričao o tome kako još uvek imam lepe uspomene na naše zajedničko putovanje na Jadransku obalu, i ostrvo Korčulu, kada mi je bilo pet godina. Sve je bilo obasjano svetlošću u mom sećanju; jasno se sećam uživanja na plaži i suncu. Njihova reakcija me je iznenadila – rekli su mi da je za njih to bila najgora noćna mora! Otkud to? Zato što, u momentu kada je autobus došao do obale, ja sam istrčao, i sa platforme skočio u duboko more! Svi u autobusu su vrištali užasnuti, a moj otac je u odelu skočio u more – do poslednjeg momenta, nisu znali da li ću preživeti. Bio sam zaprepašćen! Moj mozak je očigledno izbrisao ovaj traumatični doživljaj iz mog pamćenja. Kako sam uopšte došao na ideju da skočim u moguću smrt, u tom uzrastu, teško je dokučiti.

Još jedan susret sa smrću desio se kada mi je bilo oko 20 godina, u vreme dok sam, kao i svi mladići u to vreme, služio vojni rok dug godinu ipo u JNA. To je bilo kolosalno gubljenje vremena, između ostalog i zato što su mnoge vežbe bile kreirane po uzoru na „herojsku borbu iz Drugog svetskog rata“, što je bilo daleko od načina na koji se vodilo moderno ratovanje čak i tada, osamdesetih. Usred ledenog decembra, krenuli smo na 70 km dug marš ka bosanskim planinama, a kad smo se tamo zatekli iskopali smo rupu duboku jedan metar i razastrli šator iznad, i to je bilo mesto gde smo provodili noć… Sećam se da sam se tokom dve noći tresao od hladnoće, sve do momenta kada bih doživeo najčudnije blaženstvo, nešto poput nirvane, kada više nisam osećao mraz… To blaženo stanje uvek su prekidali vojnici, koji su dolazili da nas probude. Kada sam, mnogo godina kasnije, to ispričao prijatelju koji je medicinski tehničar, on je objasnio da sam zapravo iskusio momente na pragu umiranja – u poslednjoj fazi smrzavanja, organizam aktivira poslednje zalihe energije.

Eto, tako su izgledali moji skromni susreti sa smrću… U novije vreme, razmišljao sam o vezi između ličnih iskustava i konceptima koji se smišljaju na kolektivnom nivou. Život u Srbiji me je naučio da, recimo, tehnologija, kao i moda ili kulturni trendovi, i mnoge druge stvari, bivaju oblikovani u razvijenim zemljama,a tek nakon toga se pojavljuju imitacije u perifernim krajevima kao što je Balkan. To je učinilo da kolektivne psihe stanovništva malih zemalja zauzmu inferioran stav : veruju da im je suđeno da zauvek ostanu epigoni, i – radije nego da tragaju za svojim načinima da reše vlastite probleme, ostaju pasivni dok čekaju da rešenja dođu odnekud sa strane. To je bilo vidljivo tokom globalne panike uzrokovane kovidom 19 – čak i ako je to sve poniklo u Kini, reakcija na pandemiju je svakako projektovana na Zapadu. U zemljama kao što je Srbija, uglavnom se čekalo i zatim podražavalo ono što su drugi činili. U svakom slučaju, upravo to je bio mehanizam koji je pandemiju učinio globalnim fenomenom, koji se širio preko granica država i kultura.

I – čak iako je to bilo za očekivati, sa zanimanjem sam posmatrao kako je ta situacija uticala da se velikom brzinom širi strah od smrti. Zato što, budimo iskreni – smrt nije tema o kojoj se tako često govori u Zapadnom svetu. Mogućnost da umrete od posledica tajanstvene bolesti, sami i u izolaciji, daleko od udobnosti doma i okruženi ljudima u svemirskim odelima (koji vas tretiraju kao opasnost po okolinu), je scenario koji podstiče najgore strahove.

(Sa engleskog preveo autor)

Teilen