Distance Learning

Ilang linggo na lamang at matatapos na ang school year ng panganay kong anak. Kinapapanabikan niya ang pagtatapos na ito. Naiintindihan ko siya. Hindi rin naman kasi naging madali ang pag-aaral sa panahong ito na ikinulong ang mga bata sa kani-kanilang bahay.

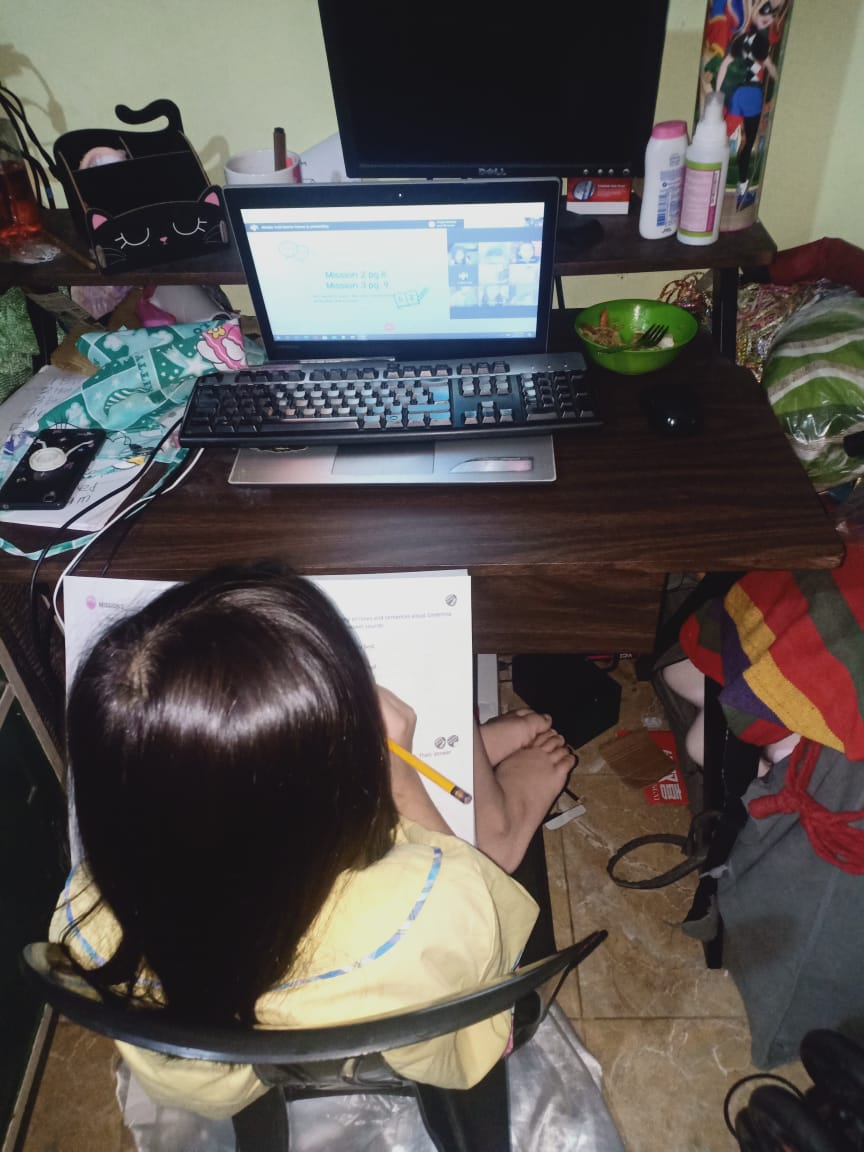

Dahil sa pandemya, napilitan ang mga paaralan dito sa Pilipinas na lumipat sa distance learning. Ang mga eskuwelahan na binubuhay ng halakhak at paglalaro ng mga bata ay isa nang labi ng karunungan. Sa kaso ng aking anak, online ang naging medium ng kanilang klase. Ang pagsusulit ay isa na lamang link sa internet. At ang mga kaniyang mga guro at kaklase ay maliliit na kuwadro ng mukha sa screen ng computer.

Kung tutuusin, masuwerte pa nga ang aking anak, at may malinaw at maayos siyang koneksyon ng internet sa loob ng aming bahay. Bilang isa sa may pinakamabagal ngunit mahal na internet connection sa South East Asia, inaasahan ang samu’t saring problemang kahaharapin ng mga estudyante sa kanilang online classes. May mga estudyanteng kinailangang umakyat ng puno o tumahak sa mga liblib na mga bundok makasagap lamang ng disenteng koneksyon para makadalo sa kanilang mga klase o makapagpasa ng kanilang takdang-aralin. Karagdagang gastos din sa pamilyang pinaralisa ng pandemya at kuwarantina ang pagbili ng mga bagong gadget at pagpapakabit ng internet.

Katulad ng pagtugon ng aming pamahalaan sa pandemya, hindi pinaghandaang mabuti ng kagawarang nangangasiwa sa edukasyon ang implementasyon ng distance learning. May malalayong bayan sa bansa ang hindi pa naaabot ng teknolohiya ng internet ang umaaasa sa modules na kung hindi minadali ang paggawa, mali-mali naman ang itinuturo. Madalas, abonado pa ang mga guro sa pagpapa-print out sa mga ito. Noong isang linggo, napanood ko ang video ng isang grupo ng mga guro na napilitang tumawid sa maalon na laot madala lamang ang mga module sa kanilang mag-aaral. Hindi naman nakapagtataka, lagi namang huli sa prayoridad ng mga politiko ang edukasyon ng mga kabataan.

Sa bahay, napansin ko ang pagbabago sa ugali ng aming panganay. Bago ikinulong ng distance learning, palakaibigan siya at bibo sa klase. Naaalala ko ang huling pagtatanghal niya sa buong eskuwelahan. Kasama siya sa isang dula. Gumanap siya bilang isang pato na nag-aaliw sa bugnuting haring leon. Umaawit siya at sumasayaw para pangitiin ang nakasimangot na pinuno. Selebrasyon ito para sa buwan ng mga libro. Natatandaan ko ang ningning sa kaniyang mata. Wala itong ipinagkaiba tuwing nagkukuwento siya tungkol sa nangyari sa kaniya sa paaralan: ang gasgas sa tuhod na nakuha sa pakikipaghabulan sa kaibigan, ang bago niyang guhit na itinuro ng kaklase, at ang masaya nilang tawanan ng katabi.

Nawala na ang sigla at galak niyang ito. Madalas, aburido siya. Bugnutin. Palibhasa kasi nawalan siya ng tunay na interaksyon sa mga kaibigan at kaklase. Bawat umaga, walang gana siyang haharap sa computer para makinig sa paputol-putol na lektura ng kaniyang guro. Para sa kaniya, isa na lamang itong gawain na hindi niya kinapapanabikan.

Naikuwento din minsan ng katrabaho ang danas din niya sa anak na may online class. Napansin niya ang kawalang gana nito sa pag-aaral. Biro ko nga, hindi lamang pagkatuto ang dahilan kung bakit tayo pumapasok sa paaralan, nandito rin tayo para makipaghalubilo at makipagkapwa-tao. Dahil sa pandemya, nalimitahan din ang mga bata na bumuo ng isang malusog na ugnayan sa kapwa nila bata.

Nakaisang taon na ang lockdown. Biglang lumobo ang bilang ng mga tinamaan ng corona. Mukhang ipagpapaliban ulit ang pagkakaroon ng face to face class. Hindi ko maiwasang malungkot para sa anak ko. Nalulungkot ako para sa mga kapwa niya bata. Nalulungkot ako para sa kanilang henerasyon na wala na silang ibang mapagkukuwentuhan tungkol sa karanasan nila sa pag-aaral maliban sa estatikong mukha ng kanilang guro na biglang naputol ang koneksyon ng internet, at ang mga nalamog na module at work book.

Fernunterricht

In nur wenigen Wochen geht das Schuljahr meiner ältesten Tochter zu Ende. Sie kann es kaum erwarten. Ich verstehe sie. In diesen Zeiten ist es für Kinder nie einfach zu lernen, wenn sie zu Hause eingesperrt sind.

Aufgrund der Pandemie mussten die Schulen auf den Philippinen auf Fernunterricht umsteigen. Die Schulen, die einst durch das Lachen und Spielen der Kinder belebt wurden, sind zu Relikten des Wissens geworden. Asynchrone und synchrone Klassen sowie symptomatische und asymptomatische Fälle sind jetzt Teil unseres Wortschatzes. Prüfungen sind heute nur Links. Und Klassenkamerad·innen und Lehrer·innen reduziert auf kleine, gerahmte Gesichter am Computer.

Tatsächlich hat meine Tochter das Glück, dass sie zu Hause eine gute und stabile Internetverbindung hat. Unser Land ist bekannt für das langsamste, aber teuerste Internet in ganz Südostasien. Daher werden Schüler·innen hier während ihres Online-Unterrichts mit einer Vielzahl von Problemen konfrontiert. Es gibt Schüler·innen, die auf Bäume klettern oder auf entlegene Berge steigen, nur um eine anständige Verbindung zu haben – denn ohne die können sie weder am Unterricht teilnehmen noch ihre Hausaufgaben machen. Darüber hinaus ist es eine zusätzliche finanzielle Belastung für Familien, die von Pandemie und Quarantäne eingeschränkt sind, neue Geräte zu kaufen und Internet zu installieren.

Wie die Reaktion unserer Regierung auf die Pandemie hat auch das Bildungsministerium die Umsetzung des Fernunterrichts nicht richtig geplant. Es gibt viele entlegene Dörfer im Land, die kein Internet haben. Sie stützen sich nur auf Module, die nicht nur hastig zusammengeschustert, sondern auch voller Fehler sind. Oft müssen die Lehrer·innen die Druckkosten dafür tragen. Letzte Woche habe ich ein Video einer Gruppe von Lehrer·innen gesehen, die die raue See überquerte, um ihren Schüler·innen Module zu bringen. Es ist nicht allzu überraschend, denn die Jugendbildung steht bei den Politiker·innen immer an letzter Stelle der Prioritätenliste.

Zu Hause bemerkte ich einige Verhaltensänderungen bei meiner Ältesten. Bevor der Fernunterricht sie einsperrte, war sie sehr freundlich und aktiv im Unterricht. Ich erinnere mich an die letzte Theateraufführung an ihrer Schule. Sie spielte eine Ente, die den übellaunigen Löwenkönig unterhielt. Sie sang und tanzte, um den stirnrunzelnden Anführer zum Lächeln zu bringen. Mit dem Stück feierte die Schule den Monat der Bücher. Ich erinnere mich an das Funkeln in ihren Augen. Egal, was sie von der Schule erzählte – ob von der Wunde am Knie, die sie sich beim Spielen mit ihren Freund·innen zugezogen hatte, von der neuen Zeichnung, die sie der Klasse beigebracht hatte, oder vom fröhlichen Gekicher mit ihren Sitznachbar·innen.

Mit der Pandemie sind Freude und Zufriedenheit verschwunden. Die meiste Zeit ist sie gereizt und launisch, weil ihr der Kontakt zu Freund·innen und Klassenkamerad·innen fehlt. Morgens hat sie keine Lust mehr, sich vor den Computer zu setzen, um den abgehackten Vorträgen der Lehrer·innen zuzuhören. Für sie ist das eine von vielen Aktivitäten, die ihr keinen Spaß machen.

Eine Arbeitskollegin erzählte mir, dass ihr Kind auch online lernt – und jegliches Interesse am Lernen verloren hat. Ich scherzte, dass Lernen nicht der einzige Grund ist, warum wir zur Schule gehen. Wir besuchen sie auch, um Kontakte zu pflegen und andere kennenzulernen. Die Pandemie hindert Kinder daran, gesunde Beziehungen zu Gleichaltrigen aufzubauen.

Wir sind seit einem Jahr im Lockdown. Und jetzt ist die Zahl der Infizierten dramatisch gestiegen. Es ist wahrscheinlich, dass der Präsenzunterricht weiter verschoben wird. Ich kann nicht anders, als traurig für meine Tochter zu sein. Es tut mir leid für Kinder wie sie. Es tut mir leid für ihre Generation, die nichts mehr zu erzählen hat – nur vom eingefrorenen Gesicht ihres Lehrers, der aufgrund eines schlechten Signals unterbrochen wurde, und von zerlesenen Modulen und Arbeitsbüchern.

Übersetzung: Elmer Grampon

Lektorat: Iris Thalhammer

Distance Learning

In just a few more weeks, my eldest daughter’s school year will end. She has been expectantly waiting for it to be over. I understand her. It’s not so easy to study in times like these when children are locked-up in their homes.

Because of the pandemic, schools in the Philippines were forced to shift into distance learning. The schools that had once been livened up by children’s laughter and frolic have become relics of knowledge. Asynchronous and synchronous classes have now entered our vocabulary as well as symptomatic and asymptomatic cases. Their quizzes were now mere links. And their classmates and teachers reduced to small, framed faces on the computer.

In all honesty, my daughter is lucky in that she has a good and stable internet connection in our house. In a country with the slowest yet most expensive internet connection in South East Asia, students are expected to encounter all sorts of problems with their online classes. There are students who need to climb up trees or tread to remote mountains just to have a decent connection so that they could attend their classes or submit their homework. For families paralyzed by the pandemic and quarantine, procuring new gadgets and installing an internet connection were additional expenses.

Much like our government’s response to the pandemic, the government department for education hasn’t properly planned the implementation of distance learning. There are remote towns in the country where internet technology hasn’t reached yet and are dependent on modules which, if they weren’t hastily done, taught the wrong things. The teachers themselves often need to spend for the printing of these materials. The other day, I watched a video of a group of teachers who had to cross a wavy sea just to deliver the modules to their students. It’s not all that surprising—the education of the youth always falls last on the politicians’ priority.

At home, I noticed a change in my daughter’s mood. Before being caged in distance learning, my daughter loved making friends and being participative in class. I still remember her last presentation in front of the entire school. She was part of a play. She played the duck who entertained the cranky lion king. She sang and laughed just to make the frowning chief smile. This was held to celebrate Book Month. I remember the sparkle in her eyes. This was no different from when she shared her experiences in school: the gash on her knee she incurred running after her friends, her new drawing she taught the class to make, and the joyous giggling she had with her seatmates.

When the pandemic hit, her radiance and cheerfulness receded. She became ill-tempered. Grumpy. The reason being that she no longer had actual interaction with her friends and classmates. Every morning, she’d face the computer apathetically to listen to her teacher’s choppy lectures. For her, it became just one of the activities she had no passion for.

A coworker had once told me that she too had a child taking online classes. She noticed that her child had lost all interest in studying. I joked that it was not only the lessons which made us to go to school but we are here to interact and to get to know others. Due to the pandemic, children have also been prevented from forming healthy relationships with their peers.

It has now been one year of lockdown. The number of corona virus cases has surged suddenly. It seems that once again face to face classes would be forestalled. I couldn’t help but feel sorry again for my daughter. I feel sorry for other children like her. I feel sorry for their generation who had no other story to tell about their learning experiences apart from the static face of their teacher being interrupted by an internet disconnection, and their battered modules and work books.

Translation: Bernard Capinpin

Teilen