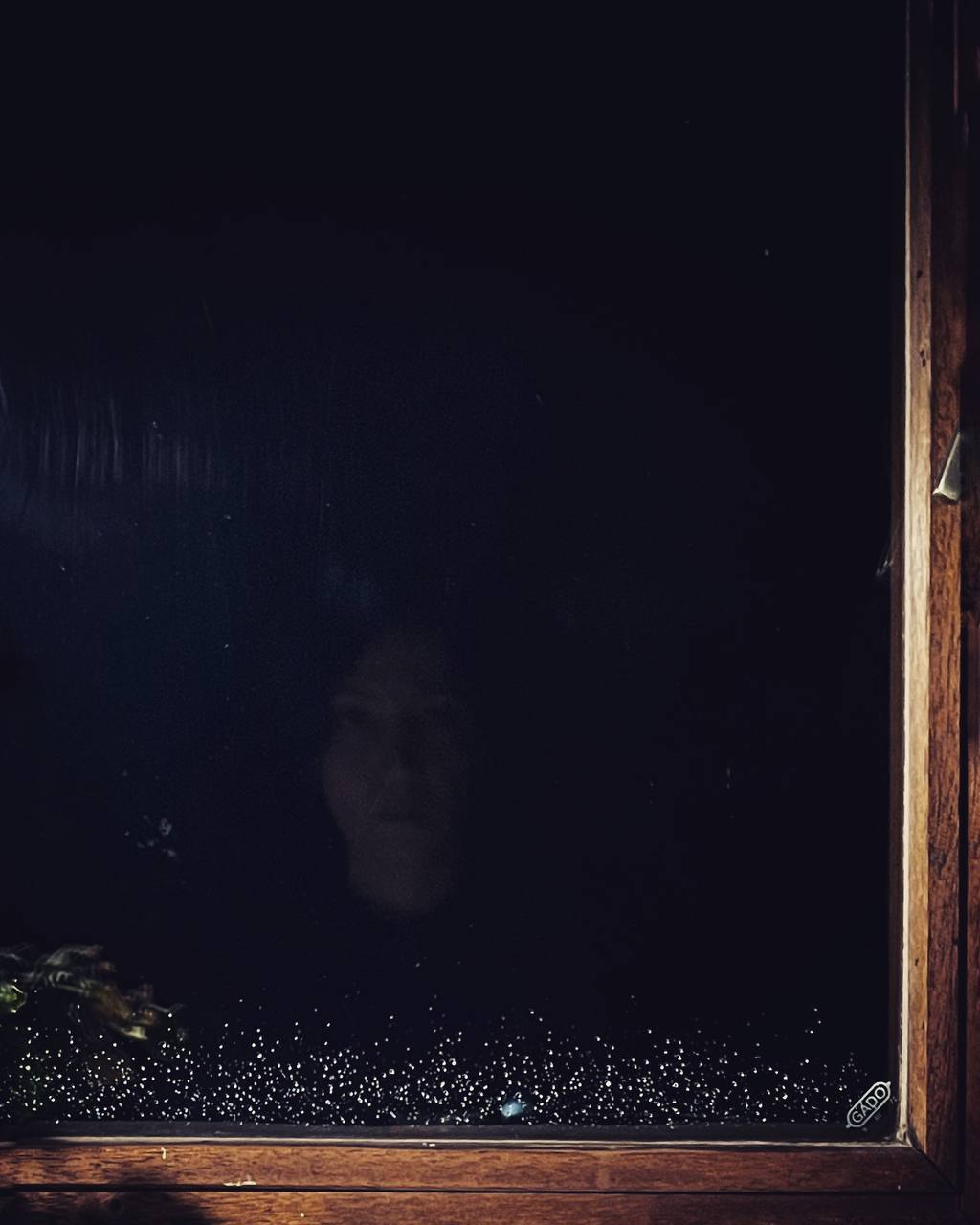

من هر روز میمیرم

پشت پنجره صدای باران است، و یادم نیست که همیشه چشمانتظار کوبیدنش بودم که بهخوابم ببرد. ایستادهام پشت صدای باران و خیرهام به تصویری که در تاریکروشنِ شیشه از من پیداست. پیداست که نمیشناسمش. به چهرهی محو و نیمهتاریک روی نیمهروشنِ شیشه زل زدهام و نمیفهمم چرا اینجاست. نمیفهمم چرا چشمهای سارینا نباید جای این زنِ شکسته، روی روشنای بارانی شیشه باشد. ولی میفهمم که اینکه میبینم نباید در این امنیت باشد. نمیفهمم چرا به جای این زنِ مرده، نباید صدای خندههای نیکا توی خیابانهای رهای اینجا بپیچد. نیکا که میخواست برای دیدن دوستش به آلمان بیاید. اما میفهمم نباید خندید. هربار به اجبار چشمم به آینهی روشویی میافتد، کشتهشدههای آن روز را مرور میکنم؛ نمیفهمم چرا خدانور به جای تو اینجا نیست؛ چرا اسرا، چرا کیان، چرا حمیدرضا، چرا مونا اینجا نیستند. اما میفهمم نباید زندگی کنم. زنی که تصویرش روی تاریکروشنِ شیشهی بارانخورده افتاده، شصت شب گذشته را بدون قرص نتوانسته بخوابد. تکوتوک شبهای بیقرص هم کابوسهای توفانی و پشتبهپشت بوده. روزهاست که پاییز پشتِ پنجره هر روز رنگ عوض میکند و یادش نیست که زمانی شیدای پاییز و رنگهاش بوده. گاهی اگر به وقتِ سیگارِ پشت پنجره، چشمش به شیدایی رنگها بخورد، بهآنی رو برمیگرداند که خیانت است؛ دیدن زیبایی خیانت است؛ خواب و خنده خیانت است. حالا که آنجا نیست، هر چیزی اینجا خیانت است. وقتی اینهمه زیبایی هر روز به خاک میرود، بودنش حتا اینجا خیانت است،. نمینویسد که نوشتن هر کلمه حتا خیانت است. تصویر زنِ تکیدهی روی روشنای شیشهی بارانی را میبینم که وعدهی قرص شبِ شصت و یکمش را میبلعد و دست به لیوان آب میبرد؛ تا فردا که خاک روی چهرهی دیگری بریزد…

Ich sterbe tagtäglich

Draußen klopft der Regen ans Fenster, und ich weiß gar nicht mehr, dass es Zeiten gab, in denen ich dieses Klopfen herbeigesehnt habe, damit es mich in den Schlaf wiegte. Ich stehe am Regenklopfen und starre auf mein Spiegelbild im Zwielicht der Fensterscheibe. Es ist mir sichtlich fremd. In der halbhellen Scheibe sehe ich halbdunkel und verschwommen mein Gesicht und weiß nicht warum. Ich frage mich, weshalb ich in der regennass funkelnden Scheibe statt dieser gebrochenen Frau nicht Sarinas Augen sehe. Ich weiß aber, ich sollte all das nicht in Sicherheit sehen. Ich frage mich, warum hört man statt dieser toten Frau in den freien Straßen hier nicht Nikas Lachen? Nika, die ihre Freundin in Deutschland besuchen wollte. Ich weiß aber, dass man nicht lachen soll. Wann immer ich, notgedrungen, in den Spiegel überm Waschbecken schaue, gehen mir die an dem Tag ermordeten Menschen durch den Sinn. Ich frage mich, weshalb statt mir nicht Khodanur hier ist? Weshalb Esra, Kian, Hamid-Reza, Mona nicht hier sind. Ich weiß aber, dass ich nicht leben soll. Die Frau, deren Gesicht sich im Zwielicht der regennassen Scheibe spiegelt, kam in den vergangenen sechzig Nächten nicht ohne Schlaftabletten aus. Manche Nächte ohne Tabletten waren wilde Alpträume, ohne Ende. Manchmal wechselt der Herbst draußen vorm Fenster täglich seine Farben, und sie hat ganz vergessen, wie hinreißend sie den Herbst und seine Farbenpracht einst fand. Bisweilen, wenn sie rauchend am Fenster steht und draußen das faszinierende Farbenspiel sieht, wendet sie den Blick ab, weil er Verrat ist; Schönheit sehen ist Verrat; schlafen und lachen sind Verrat. Weil sie nicht dort ist, ist hier alles Verrat. Wenn dort Tag für Tag so viel Schönes begraben wird, ist selbst ihr Hiersein Verrat. Sie schreibt nicht, weil jedes Wort, das sie schreibt, Verrat heißt. In der vom Regen nassen Scheibe sehe ich die erschöpfte Frau die Verheißung ihrer einundsechzigsten Schlaftablette schlucken und nach einem Glas Wasser greifen; morgen wird wieder ein Gesicht mit Erde zugeschüttet…

Übersetzung: Jutta Himmelreich

I die everyday

There is the sound of rain outside the window, and I don’t remember always waiting for it to knock to put me to sleep. I am standing behind the sound of the rain and I am staring at the image of me in the dark light of the glass. It seems that I do not know it. I have stared at the faded and half-dark face on the half-bright glass and I don’t understand why it is here. I don’t understand why Sarina’s eyes shouldn’t be on the rainy glass instead of this broken woman. But I understand that what I see should not be in this security. I don’t understand why, instead of this dead woman, the sound of Nika’s laughter shouldn’t be heard in the streets here. Nika wanted to come to Germany to meet her friend. But I understand you shouldn’t laugh. Every time I force my eyes to look at the vanity mirror, I review the people killed that day; I don’t understand why Khodanour is not here instead of you; Why Esra, why Kian, why Hamidreza, why Mona are not here. But I understand that I should not live. The woman whose image fell on the dark light of the rain-stained glass has not been able to sleep for the past sixty nights without pills. The occasional pill less nights were stormy nightmares back-to-back. For days, autumn behind the window has been changing colors every day, and she does not remember that she was once obsessed with autumn and its colors. Sometimes, if her eyes fall into a frenzy of colors while smoking a cigarette by the window, she turns it back to the one that is treason; Seeing beauty is betrayal; Sleep and laughter are betrayal. Now that she’s not there, anything here is treason. When so much beauty goes to the ground every day, her being even here is a betrayal. She does not write that writing every word is treason. I see the image of the woman staring at the light of the rain glass, swallowing her 61st night pill and reaching for a glass of water; Until tomorrow when she pours dirt on another’s face…

Translation: Andisheh Karami

Teilen