The (Ideal) Postsocialist Woman?

The (Ideal) Postsocialist Woman

Alternative images of women, emancipation, and feminism – or the traditional image of women, motherhood and self-sacrifice? The interpretation concerning how an ideal woman should be in the former socialist countries of Europe is often ideologically heated. A debate hardly seems possible. In this essay, we take a more objective, yet at the same time very personal and therefore partial look at the phenomenon of the ‘post-socialist woman’.

The three artists

Fedulova, Belorusets and Kalwat have been invited to contribute as precise observers of their own generation, always with focus on individuals. They trace the lived images of women in a variety of artistic ways, whether in documentary form, in a mixture of documentation and fiction, or as pure fiction. In doing so, they draw a contrasting, contradictory picture of their generation – a hybrid generation that spent its childhood in a socialist state but was then confronted with the ‘West’ in its youth, due to the political turn of 1989.

Yevgenia Belorusets

Yevgenia Belorusets lives and works in Kiev and Berlin. She is co-founder of Prostory (2017), a newspaper for literature and art, and has been a member of the curatorial group Hudrada since 2009. She works with photography and critical writing at the intersection of art, literature, and social activism – this includes participation in the National Pavilion of Ukraine at the Venice Biennale (2015) and the Kiev Biennale (2015, 2017), among other forums. Since 2014, she has been involved in human rights initiatives in eastern Ukraine. Her book »Happy Fallings« (»Glückliche Fälle«, Matthes & Seitz, 2019) was published in 2019 and was awarded the International Literature Prize in 2020.

Yevgenia Belorusets © Olga Tsybulskaja

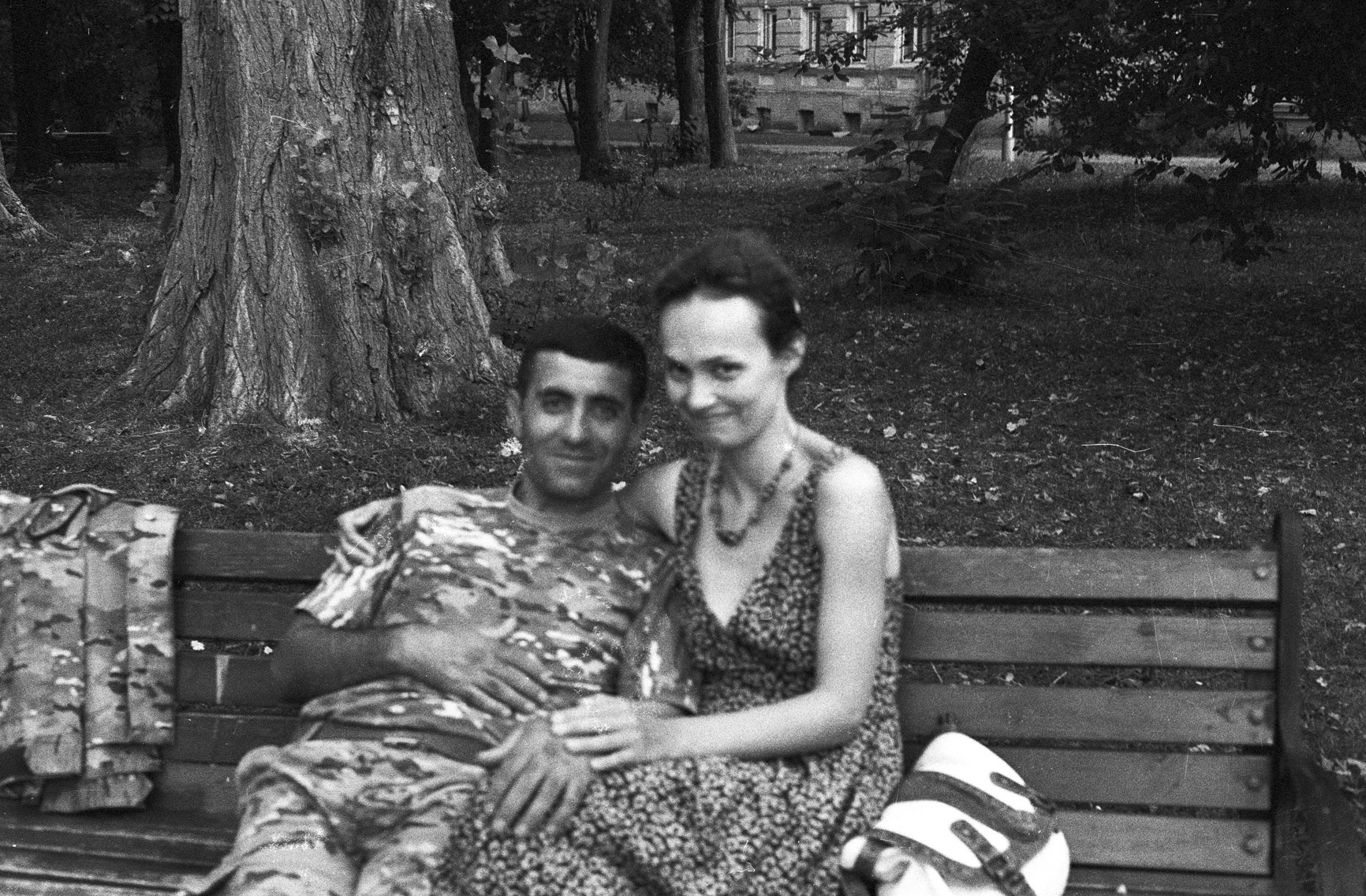

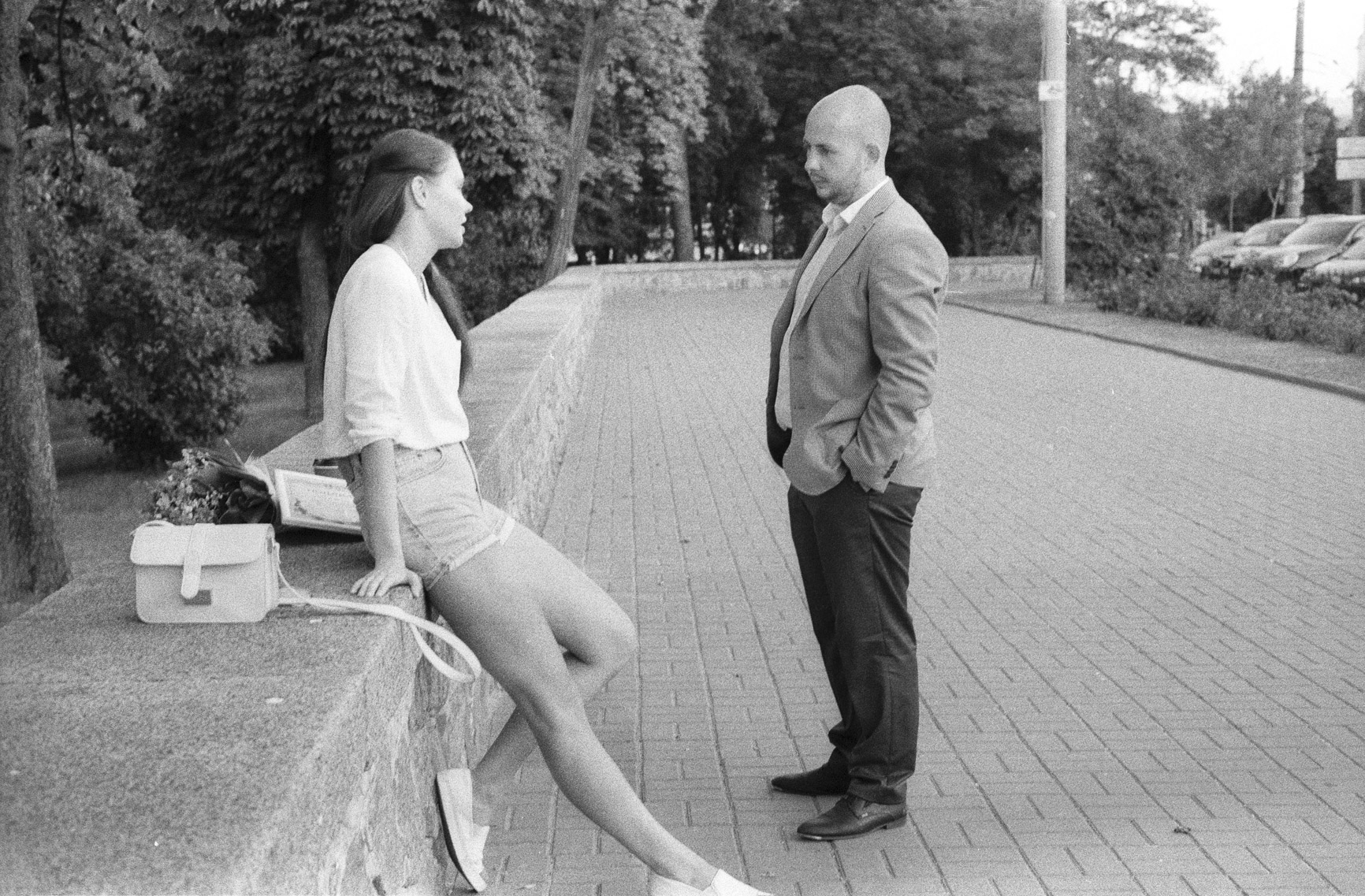

In her book »Happy Fallings« (»Glückliche Fälle«, Matthes & Seitz, 2019), Yevgenia tells stories she collected in the war zone in the Donbass region. These are stories of the war as experienced by civilians. They tell of the immediate consequences to which people, especially women, are exposed. Belorusets blends documentation with fiction, and accompanies the text with photographs from her series »War in the Park« and »And I State: Yesterday has not yet begun« (both in 2017).

Yevgenia Belorusets reads from »Happy Fallings« , »8 March: The Woman Who Couldn’t Walk Any More« :

Photo from the series »War in the Park«

Photo from the series »War in the Park«

Photo from the series »War in the Park«

Katja Fedulova

Katja Fedulova was born in Russia in 1975. In 1994, move to Germany. Studies at the Muthesius University of Fine Arts and Design in Kiel, earning a degree. In 2000, she successfully applies to the German Film and Television Academy in Berlin (dffb) to study film, in which she earns a degree. She has worked as a documentary filmmaker since 2010, with a focus on modern Russia.

Katja Fedulova © Uwe Reicherter

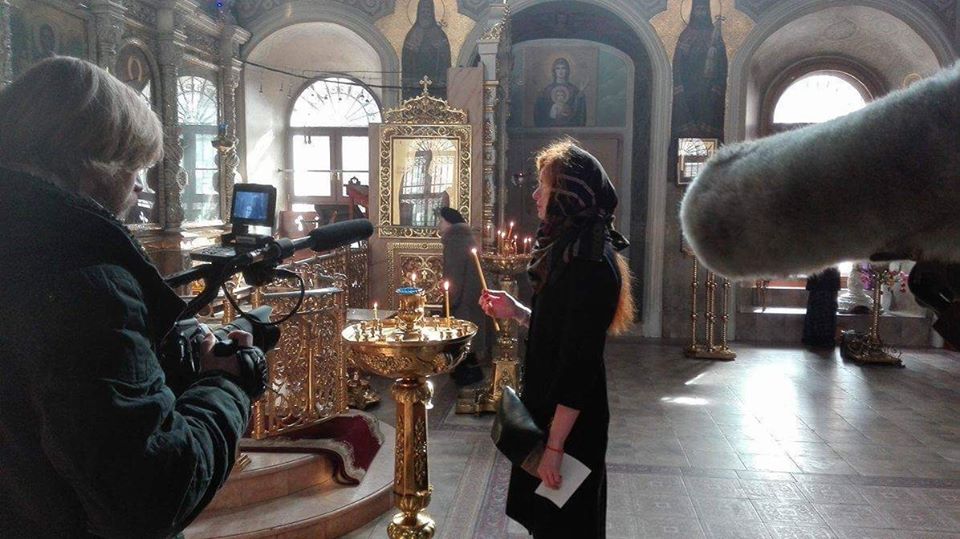

At the beginning of her film, »Three Angels for Russia: Faith Love Hope« , the story of her grandmother unfolds – a soldier in World War II. The film follows three young Russian women on their professional and political paths. In her film, the filmmaker steps out of the position of observation and positions herself in discussion with one of the protagonists.

Film still from »Three Angels for Russia«

Film still from »Three Angels for Russia«

Film still from »Three Angels for Russia«

Katarzyna Kalwat

Katarzyna Kalwat is a director and a graduate in political psychology from the Jagiellonian University in Krakow as well as from the Directing Department of the Aleksander Zelwerowicz Theater Academy in Warsaw. She is interested in processual forms and working at the interface of different artistic disciplines as well as studying the common ground between performance and theater. She is the laureate of a French Government scholarship for documentary film and the director of »Rechnitz. Opera. The Exterminating Angel« , produced by TR Warszawa.

Katarzyna Kalwat © Anna Tomczyńska

The project »Maria Klassenberg« is a combination of spectacle, installation, and exhibition. Kalwat develops the fictional figure of a performance artist, who at the same time acts as a proxy for the unknown female artists who are now being rediscovered and marketed by curators. The theatre director connects the art system of the People’s Republic of Poland with the present one.

The project »Maria Klassenberg«

The project »Maria Klassenberg«

The Artists in Conversation

The projects we see here show clearly that links with the socialist era have not been severed. The different methods and concepts employed by the three artists reflect the diversity of feminist (artistic) research. The art historian and researcher of gender studies Constance Krüger spoke to the three women:

Yevgenia Belorusets

8 March and its shifting meaning since 1989:

The role of the documentary photographer:

The significance of her life between two countries for her work as an artist:

Russian and Ukrainian identity politics during the war in Donbass:

The female voice in the short story collection ‘Happy Fallings’:

In the work of Yevgenia Belorusets, war and its experiences are centre stage, but a closer look reveals a focus on the lives and fates of women. Insisting on the female aspect of humanity is as symptomatic for the feminist debate in Eastern Europe as it is elsewhere.

Katja Fedulova

Female Soviet soldiers in WWII and female soldiers in today’s Donbass region:

Gender stereotypes in contemporary Russia, casting and camera work in “Three Angels for Russia — Faith Hope Love”:

The socialist view of women and its aftereffects:

Katja Fedulova focuses her sociological lens on real women, interlocking their lives with those of her grandmother’s war generation. Her work is driven by a biographical impulse in the spirit of the old feminist adage that the personal is political. In “Three Angels — Faith Love Hope”, we see her arguing and debating in her own film. This move to make the artist’s individual standpoint visible — a major contrast to the usual invisibility and neutrality of the documentary filmmaker—can be understood as a response to Donna Haraway’s feminist concept of ‘situated knowledges’.

Katarzyna Kalwat

About the fictional character of »Maria Klassenberg«:

The influence of Aneta Grzeszykowska on project »Maria Klassenberg«:

In the spirit of early Women’s Studies, Katarzyna Kalwat’s project sets out to discover a forgotten woman artist. There is currently a boom for this kind of archaeological project in Poland where a whole host of forgotten female artists have been unearthed in the last few years. In her fictional artistic

research, Kalwat explicitly links two periods in time, looking at the ‘patriarchal’ art scene of the People’s Republic of Poland from the contemporary point of view of two women (Kalwat and Grzeszykowska). It remains unclear whether the imagined art is historically tenable, or more like a reflection of the contemporary art scene.

We asked each of the artists to send us a picture of their childhood under socialism and an accompanying caption.

This is a picture that was taken by a professional photographer in my kindergarten. I was given clear instructions on how to stand and what to do with my hands. I look a little startled, but I think deep in my eyes you can see my anger and displeasure at the process of having my photo taken. (Yevgenia Belorusets)

Yevgenia Belorusets © privat

This is me during a ball in the summer holidays. (Katarzyna Kalwat)

Katarzyna Kalwat © privat

This is a picture of my family during a summer holiday in Tallinn, Estonia. My mother, Zoja Ivanovna Fedulova, was the head of the family. She organized everything. For example, she monitored our family finances. So we were able to go on holiday once a year. My father handed over his salary to her every month, saving only some „pocket money“ for himself, which he then spent on cigarettes, cheap wine, and beer. But he was not a drinker as long as our socialist system was in place. After the crash, my parents became unemployed. My father lost his engineering job. The state-run Urban Institute, where my mother worked as an urban architect and department head, was also closed down.

(Katja Fedulova)

Katja Fedulova © privat

Rewording feminist knowledge

In all three projects clearly demonstrate that bridges to the socialist era have not been broken. The artistic works are followed by the latest research that questions the general postulate that gender-sensitive or even feminist research did not exist during the period of state socialism. Instead of a subordinate comparison with Western theories, research is now working on the reformulation of feminist knowledge, which also takes into account the living situations and norms of the so-called Eastern Bloc. The postulate of pseudo-emancipation is thus undermined, even though the influence of, for example, tolerated women’s organizations on the development of an independent, i.e. non-partisan agenda continues to be the subject of controversy. However, an understanding of post-socialist women can only be developed when the image of socialist women in its diversity, ambivalence, and historical changeability is brought into focus – in the form of unbiased and laborious in-depth studies.

The generations of women who were socialist socialized and designated as post-socialist are made visible in the artistic works presented here, though the use of concrete examples. These are micro-studies and thus parts of a puzzle that can only be put together as a whole in the future.

Fundamentally, the question remains: How can feminist action be understood when the emancipation of women is not fought for as a grassroots movement, but is legally established by the state?

Yevgenia Belorusets © Olga Tsybulskaja

Katja Fedulova by researching

Katarzyna Kalwat © Greg Zgliński