Minsk, den 12.11.2020

Bei der Übersetzung eines Lehrbuchs für Weltliteratur feile ich gerade an einem Satz über den im Heldenepos semantisch wichtigen Kontrast zwischen Alltag und Ausnahme, Ordnung und Bruch, Routine und besonderer Aufgabe, Ruhe und tödlichem Konflikt. Das kenne ich doch aus dem jetzigen Leben in Belarus. Wie so viele verfolge ich an diesem Tag das Schicksal des 31-jährigen Roman Bondarenko, der seine Wohnung, seinen Alltag für die besondere Aufgabe verlässt, um die Stoffstreifen in Protestfarben vor vermummten ‚Ordnungshütern‘ zu schützen. Die belarussische ‚Ordnung‘ duldet keine sichtbaren Symbole des Protests im öffentlichen Raum. Roman wird so schwer verprügelt, dass er später im Krankenhaus stirbt.

Noch ein Held des belarussischen Protests. Eine Gesellschaft mit Helden ist eine ohne Routine, ohne Ruhe und ohne Alltag. Wo sind wir ohne den Schutzmantel des Alltags? Gibt es Handlungen, die auch in der haltlosen klaffenden Existenz ausführbar bleiben? Kerze anzünden? Nach Worten greifen? Welche Worte bleiben denn in der klaffenden Existenz aussprechbar? Das Auge fällt auf einen Band von Paul Celan. Er gehört zu den Autoren, von denen ich dachte, ich werde sie nie übersetzen, die wären so unerreichbar für mich. Ich kann Celans Gedichte immer lesen, aber Celan zu übersetzen ist wie Rausgehen ins offene Weltall.

„Ich gehe raus“ waren die letzten Worte von Roman Bondarenko.

Am selben Abend übersetze ich ein Gedicht von Celan, in dem es um die Schwere geht, die sich in ein Gewicht verwandelt, das die Leere zurückhält. Celans Gedicht wirkt tatsächlich wie ein Gewicht, wie ein Anker, der einen mit dem Grund verbindet, wenn man vom Strom weggetragen wird. Der Strom ist nicht weg, aber der Grund ist jetzt spürbar, auch wenn ganz im Jenseits des Alltags. Ob wir irgendwann als Gesellschaft in die Routine und Ordnung zurückfinden? Im Moment ist es wahrscheinlich zu früh, sich solche Gedanken zu machen, ich teile erstmal meinen Celan-Anker mit anderen, vielleicht ist er noch für jemanden brauchbar.

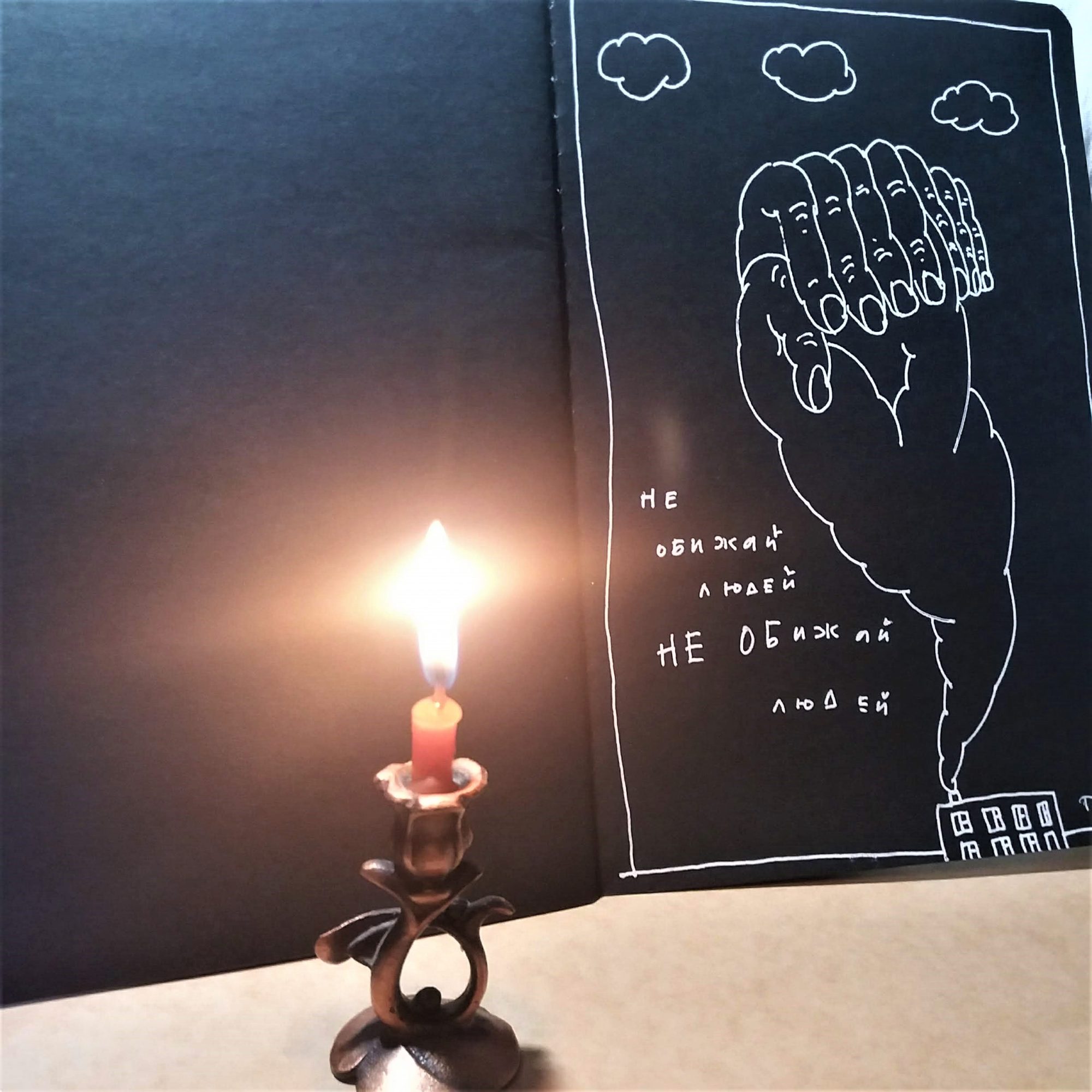

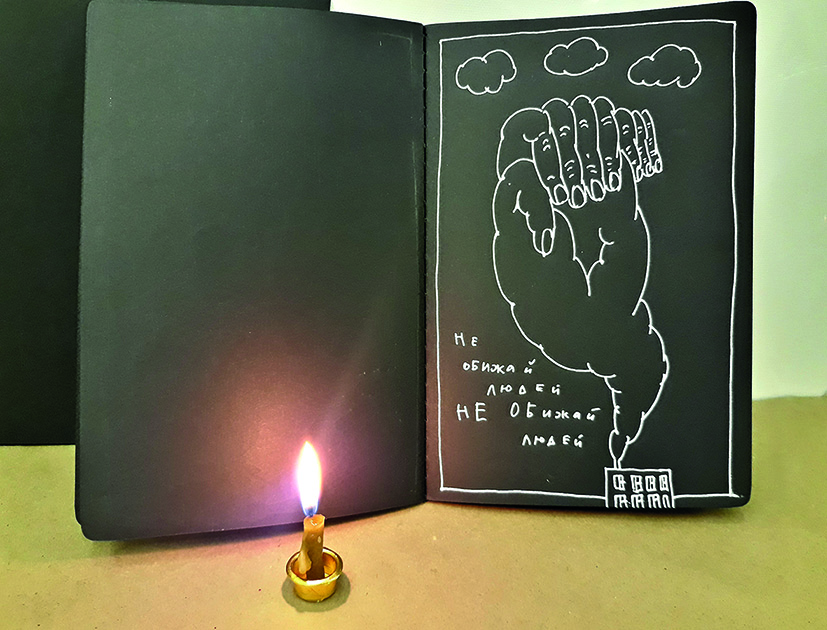

Außer dem Gedicht teile ich auf Facebook ein Foto von der Kerze, die ich wie viele andere Menschen im ganzen Land zum Gedenken an den ermordeten Roman Bondarenko anzünde. Als Hintergrund für meine Kerze wähle ich die Grafik von Antonina Slobodtschikowa, auf der geschrieben steht: „Beleidige keine Menschen“.

Minsk, 12 November 2020

In a textbook that I am translating on world literature, I am currently working on a sentence about the contrast, so important to the heroic epic, between everyday life and exception, order and breakdown, routine and special tasks, peace and deadly conflict. It is a contrast familiar to me from present-day life in Belarus. Like so many today I am following the fate of thirty-one-year-old Roman Bondarenko who left his everyday life for a special task when he went out of his flat to protect red-and-white protest ribbons from masked law enforcers. Belarusian ‘law and order’ will not tolerate visible symbols of protest in public. Roman was so badly beaten that he later died in hospital.

Another hero of the Belarusian protest movement. A society with heroes is a society without routine or peace or everyday life. What happens to us without the protective cloak of everyday life? Are there still things we can do in this flailing, gaping existence? Light candles? Clutch at words? But what words can be spoken when life gapes open? My eye falls on a book of poems by Paul Celan. He is one of those authors I have always thought beyond my reach—not someone I would ever translate. I can always read Celan, but translating Celan is like going out into space.

‘I’m going out’ were the last words of Roman Bondarenko.

In the evening I translate a poem by Celan about a heaviness becoming a weight that holds back emptiness. Celan’s poem is itself like a weight—like an anchor that keeps you grounded when the current is trying to carry you away. The current is still strong, but the solid ground is there, palpable, even if it is far off in the other world of everyday life. Will we, as a society, ever find our way back to order and routine? Just now it is probably too early to ask such questions; in the meantime, I can share my Celan anchor with others. Maybe someone can get something out of it.

As well as the poem I am sharing a photo on Facebook of a candle that I, like so many people across the country, have lit in memory of the murdered Roman Bondarenko. As a background for my candle I have chosen graphic art by Antonina Slobodchikova with the words ‘Don’t insult anyone’.

Translation: Imogen Taylor

Мінск, 12 лістапада 2020 года

Перакладаючы падручнік па сусветнай літаратуры, акурат адшліфоўваю сказ пра важны для гераічнай паэзіі кантраст паміж штодзённасцю і надзвычайнасцю, парадкам і зломам, руцінай і асобай справай, спакоем і смяротным канфліктам. Ці не тое самае зведваю зараз у Беларусі? У гэты дзень далёка не я адна сачу за лёсам 31-гадовага Рамана Бандарэнкі, які пакінуў сваю кватэру, сваю штодзённасць дзеля асобай справы – абараніць бел-чырвона-белыя стужкі ад “невядомых” у балаклавах. Беларускі “парадак” не церпіць бачных сімвалаў пратэсту ў публічнай прасторы. Рамана так моцна збілі, што пазней у бальніцы ён памёр.

Яшчэ адзін герой беларускага пратэсту. Грамадства, дзе ёсць героі, – гэта грамадства, дзе няма руціны, спакою і штодзённасці. Дзе мы апынаемся без ахоўнага покрыва штодзённасці? Ці існуюць дзеянні, якія можна выконваць у быцці, якое зеўрае, у якім няма апоры? Запаліць свечку? Звярнуцца да слоў? Якія словы можна прамаўляць у быцці, што зеўрае, дзе няма ніякай апоры? Вока выхоплівае зборнік Паўля Цэлана. Я была ўпэўненая, што ніколі не буду перакладаць гэтага вялікага паэта. Ён належыць да аўтараў, якія падаюцца мне недасягальнымі. Я шмат чытаю яго вершы, але перакласці Цэлана – гэта як выйсці ў адкрыты Космас.

“Я выходжу” – апошнія словы Рамана Бандарэнкі.

У той жа вечар перакладаю верш Паўля Цэлана, у якім вядзецца пра цяжкасць, што ператвараецца ў вагу, якая стрымлівае пустэчу. Цэланаўскі верш сапраўды ўздзейнічае як вага – якар, які злучае з дном, калі плынь зносіць цябе. Плынь нікуда не падзелася, але цяпер адчуваецца дно, хай сябе яно і зусім па той бок штодзённасці. Ці вернецца наша грамадства калі-небудзь зноў да руціны і ўпарадкаванасці быцця? Бадай, пакуль зарана пра гэта і думаць. Пакуль проста падзялюся сваім цэланаўскім якарам, можа быць, яшчэ каму-небудзь спатрэбіцца.

Апроч верша, дзялюся на Фэйсбуку яшчэ і здымкам са свечкай, якую запальваю ў памяць аб забітым Рамане Бандарэнку, як і шмат хто яшчэ з беларусаў. Пры маёй свечцы – графіка Антаніны Слабодчыкавай з надпісам “Не крыўдзі людзей”.

(З нямецкай пераклала аўтарка)

Teilen

-

19 Dienstag

19:30 UhrPoint of No Return – Stimmen aus Belarus

Texte und Gespräche mit Iryna Herasimovich, Volha Hapeyeva, Artur Klinau, Zmicier Vishniou, Alhierd Bacharevič, Julia Cimafiejeva, Viktor Martinowitsch, Irina Bondas, Andreas Rostek, Thomas Weiler, Nina Weller und Tina Wünschmann

Veranstaltungen mit Iryna Herasimovych

2021

Januar